65 min read • Automotive

Unleashing Thailand’s electric mobility potential

A comprehensive report on the future potential of EVs in Thailand

FOREWORD

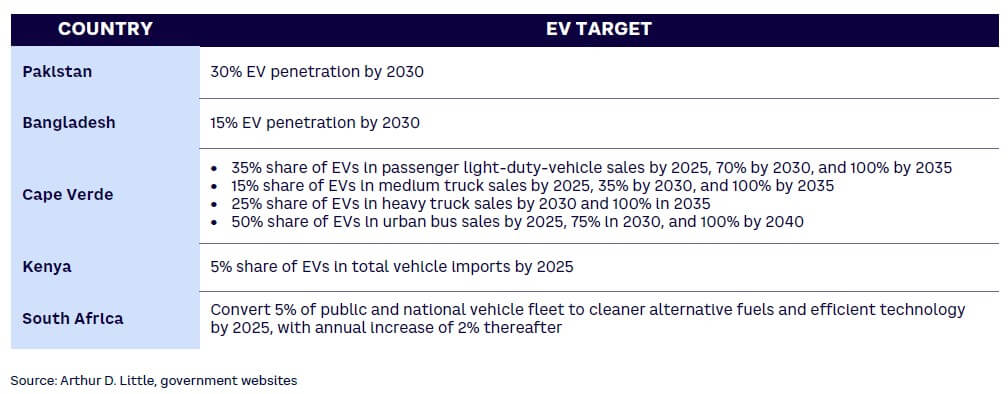

As countries around the globe prepare for carbon neutrality, the automotive industry is undergoing a fundamental transformation. At the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in October/November 2021, various nations and leading car manufacturers pledged to phase out fossil fuel–powered vehicles by or before 2040. Consequently, governments in Southeast Asia (SEA) have floated ambitious plans to capture a share of the nascent electric vehicle (EV) segment, creating various opportunities for the region — focusing on both the domestic and export markets.

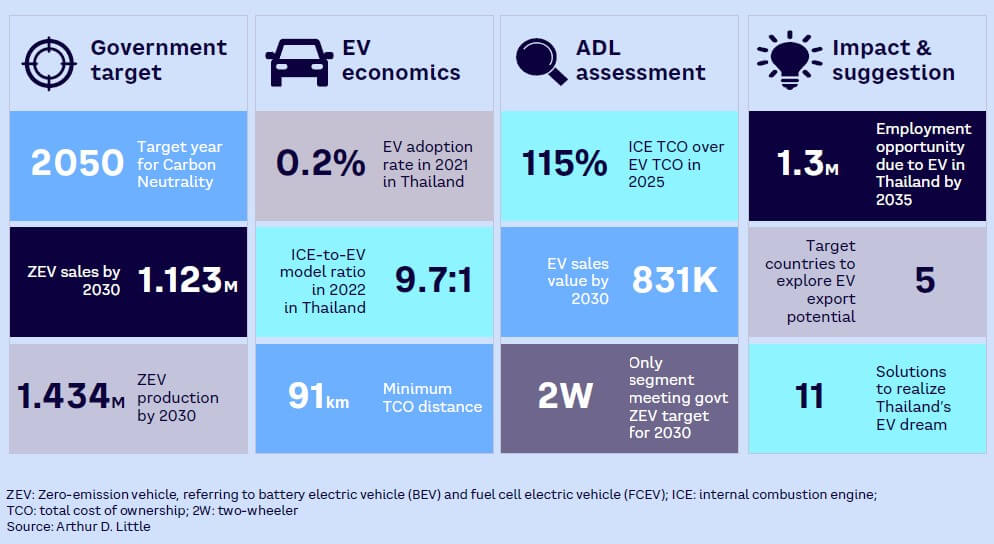

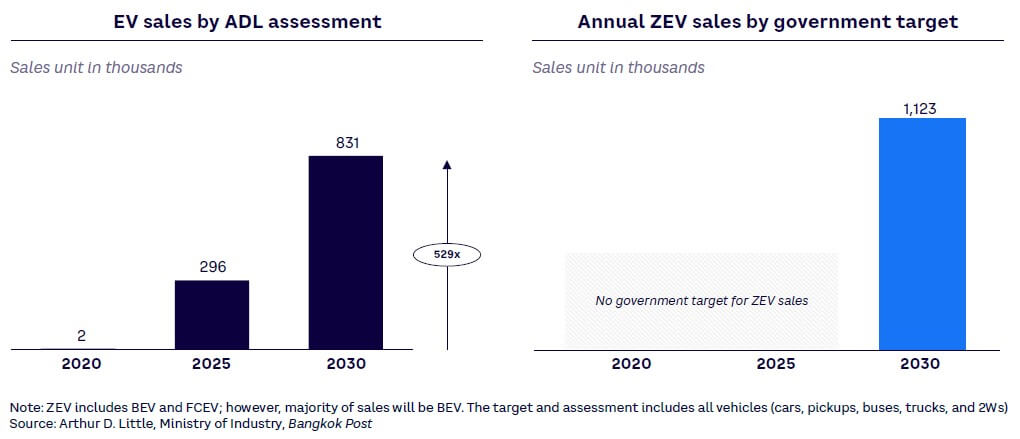

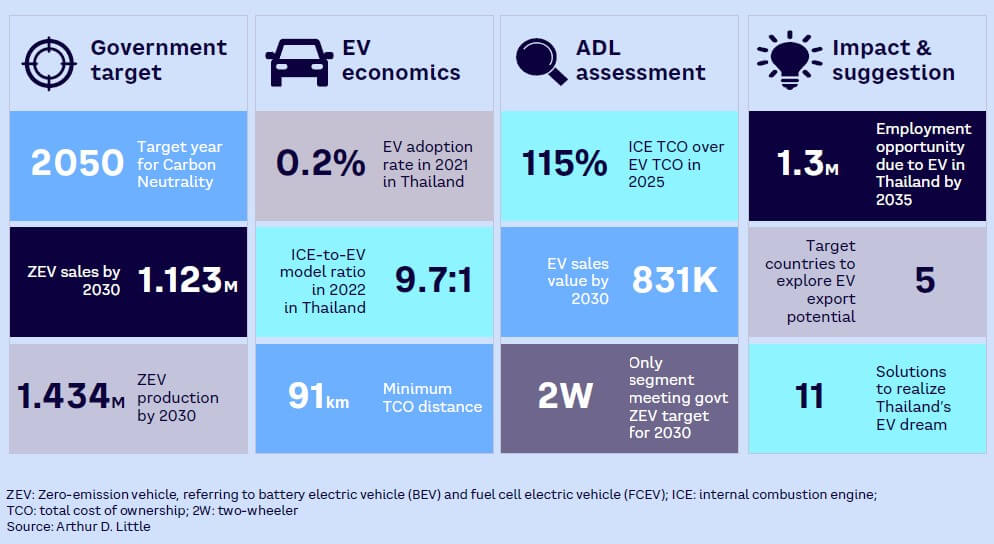

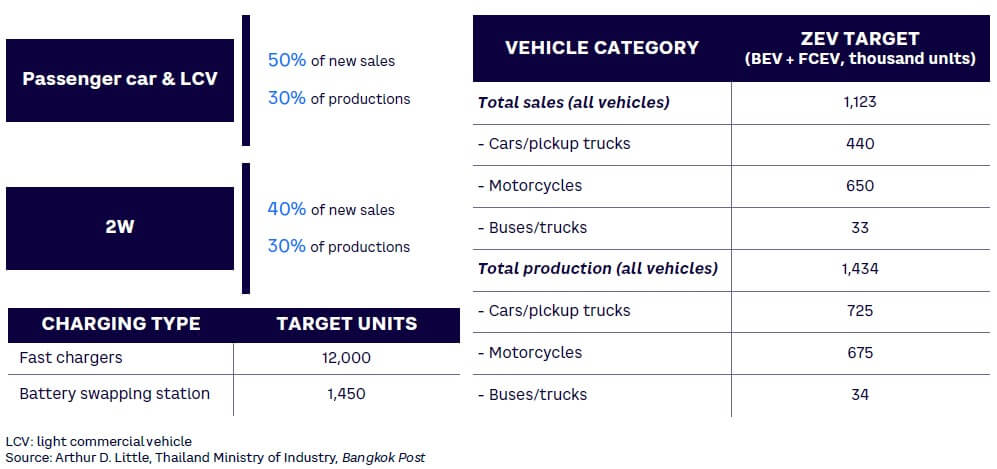

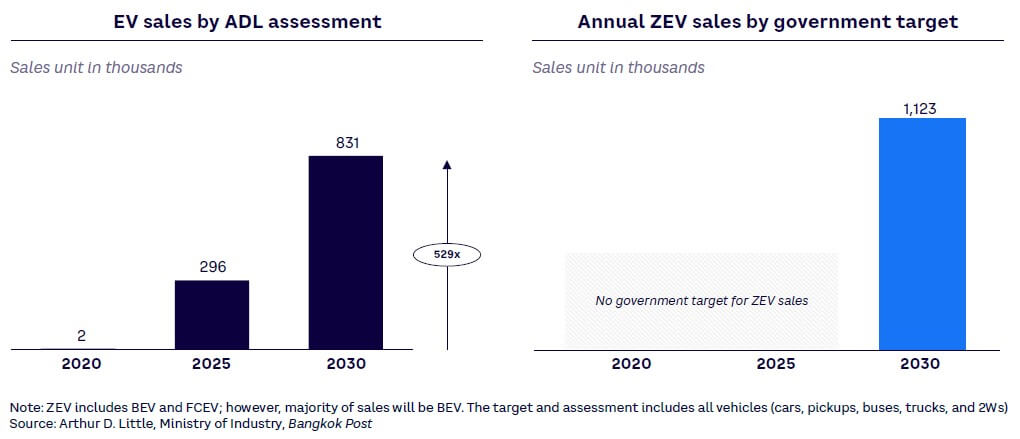

Thailand has traditionally been a strong automotive market in the region producing 2.5 million units at its peak in 2013 and — after the pandemic hit — 1.7 million in 2021. The country has now embarked on an ambitious electrification plan with the launch of its 30@30 target, which expects 30% of auto production to be electric by 2030; more specifically, 1.123 million zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs).

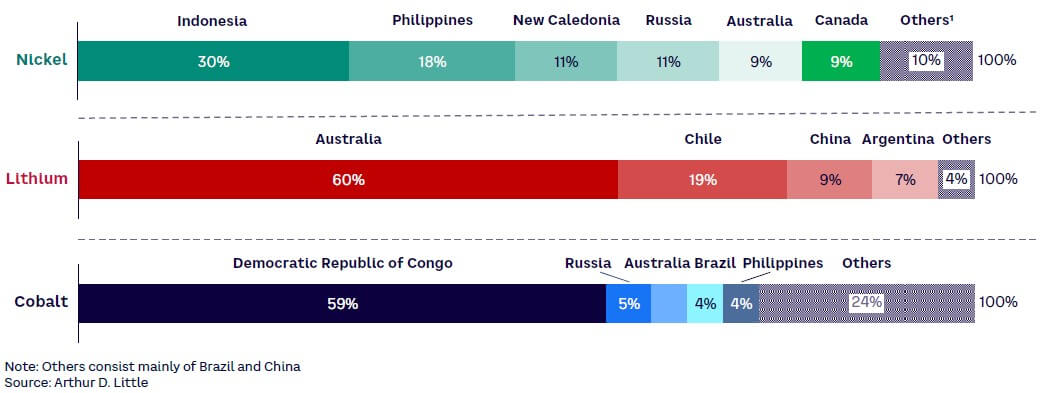

The shift toward electric mobility by Thailand, however, will have its own challenges as the other automotive powerhouse in the region, Indonesia, has access to some critical raw materials, such as nickel — a key component in lithium batteries. The export potential of Thailand as an automotive hub may also face challenges, given existing export market switches to EV from local homegrown OEMs and brands.

To support executives in automotive OEMs and new entrants in Thailand, Arthur D. Little (ADL) has analyzed the current market situation and proposes recommendations to transform Thailand’s automotive industry. Our overview of Thailand's readiness and challenges for electric mobility provides an understanding of the current situation, while our analysis of critical factors to promote EV adoption offers a broad-based structure of factors to target to transform Thailand as an EV manufacturing hub.

In this Report, we first summarize the current situation of EVs in Thailand, including a review of environmental concerns and factors behind low EV adoption rates. Next, we examine regulatory issues and market movements. Then, we identify key challenges for Thailand comparing its EV readiness index with markets around the world. The ADL EV assessment is the result of a market-based survey and some quick analysis from industry experts. Finally, we recommend a set of solutions to achieve the desired EV evolution and targets.

- Hirotaka Uchida, Head of ADL Thailand, Principal, Automotive and Manufacturing Group

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Often referred to as the “Automotive Hub of Asia,” Thailand is aiming to make the necessary transition toward the new global electrification trend. Doing so will allow the country to continue to attract foreign investment, which would move into areas of decarbonization of the transport sector, as well as contribute toward combatting air pollution. Despite various measures offered by the Thailand government, EV adoption rates are low.

LOW ADOPTION FACTORS

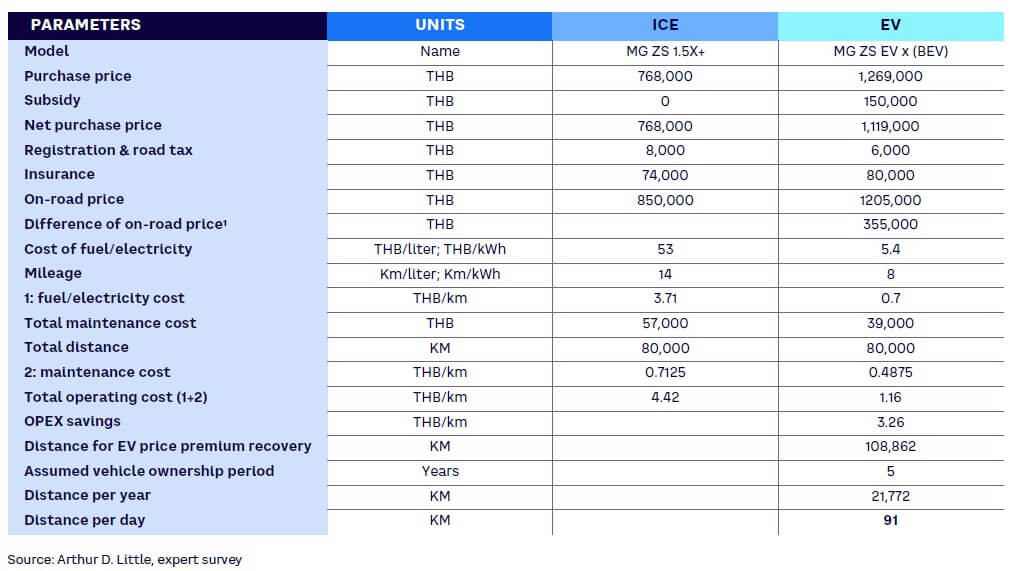

- Minimum daily distance insufficient. From a total cost of ownership (TCO) perspective, the minimum distance that a typical four-wheeler (4W) EV driver needs to drive to overcome the EV premium via savings from low maintenance and fuel costs is 91 km per day, compared to the typical driving distance of 43 km per day in the Bangkok area and 39 km per day in the provincial area, per ADL analysis. This is a key reason why EV adoption is low.

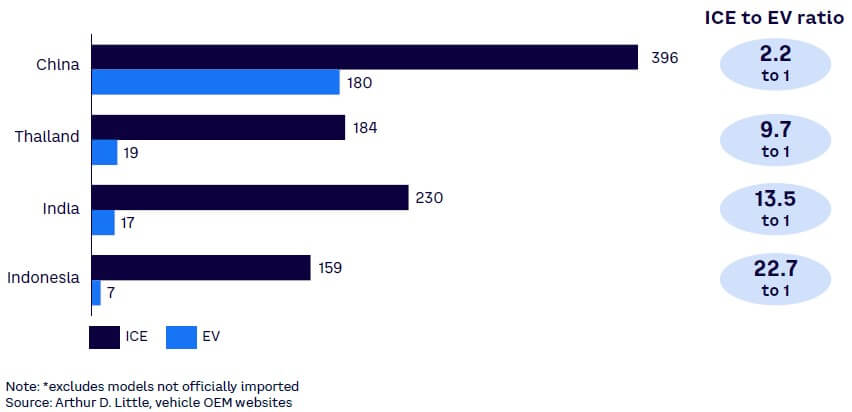

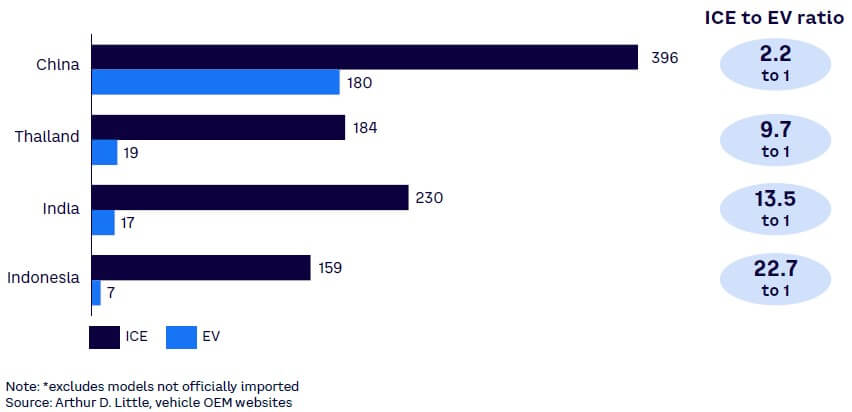

- Customers prefer choice. In 2021, the ratio of internal combustion engine (ICE) models to EVs in Thailand was 9.7:1, with countries such as China having a ratio of 2.2:1, showing comparison of model availability between ICE and EV. In addition, there is a huge price gap between the cheapest EV car model (US $22,856, post-subsidy) and the cheapest ICE car model (US $9,073). Thus, EVs are not attractive compared to ICEs in terms of model availability and pricing.

- Unfavorable macro factors hinder growth. The global shortage of semiconductor chips and COVID-19 are two key macroeconomic factors that have impeded the pace of EV adoption in Thailand. OEMs are unable to launch innovative EV models designed for the Thailand market due to the semiconductor chip shortage, while consumers find it challenging to purchase EVs due to the increased inflation rate in the last few years, excluding 2020 due to COVID and a reduction in purchasing power driven by the negative short-term economic impact of the pandemic.

- Charging infrastructure impedes adoption. Thailand’s public EV charging infrastructure (693 charging stations as of September 2021) is far behind other Asian countries, like China (1.4 million), South Korea (105K), and India (21K), which are making efforts to establish a strong EV ecosystem. Even though the government has taken numerous measures to prioritize EV charging development in Thailand, it still has a limited charging infrastructure.

REGULATORY PUSH

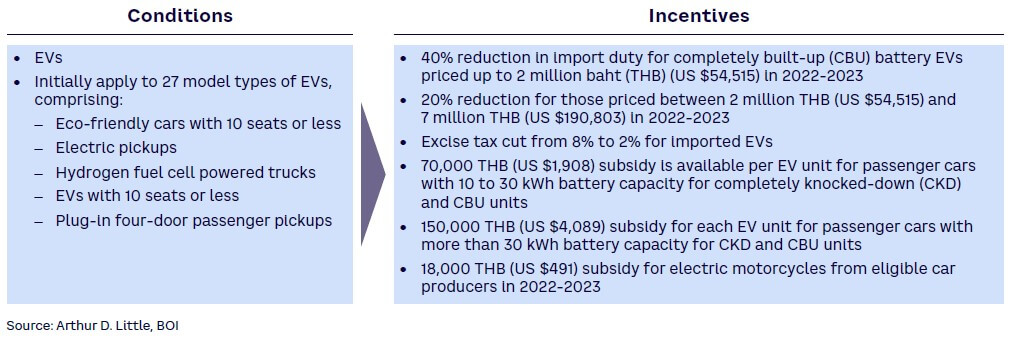

The Thailand National EV Policy Committee has introduced a roadmap as a framework for Thailand’s EV development from 2021–2035 with the aim to develop a well-established supply chain for manufacturing EVs. On the supply side, the government has set a target of 30% production of ZEVs — battery electric vehicle (BEV) and fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) — by 2030. The Board of Investment of Thailand (BOI) offers various incentives for EV manufactures, such as zero import duty for machine/raw materials and a corporate income tax (CIT) exemption for three to eight years. Moreover, BOI is also pushing for corporate tax exemptions for BEV-related components to provide more comprehensive and integrated incentives to develop the EV industry. On the demand side, in February 2022, the government announced its latest incentive package, including a reduction in import duty for completely built-up (CBU) BEVs, an excise tax cut for imported EVs, and an EV subsidy for passenger cars. In addition, the government offers a five-year CIT exemption for EV charging operators that build at least 40 chargers to support e-mobility and EV infrastructure nationwide.

MARKET MOVEMENTS

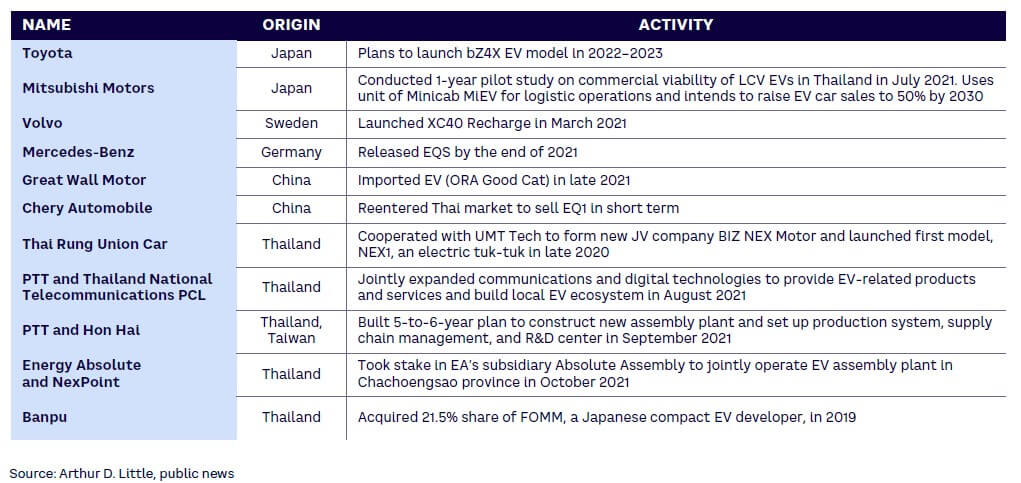

- New product launch by automotive OEMs to serve Thailand consumers. Thailand manufacturers such as Mine Mobility (Energy Absolute’s EV business) launched the first homegrown BEV (MINE SPA1) in 2020. European OEMs such as Volvo and Mercedes-Benz are enhancing their manufacturing footprints in Thailand by ramping up e-mobility. Chinese OEMs like SAIC have also prioritized their EV push in the Thailand market with the launch of EV models since 2020.

- Partnership by automotive OEMs and related industry players fosters EV ecosystem. Mercedes-Benz Thailand partnered with Thonburi Automotive Assembly Plant (TAAP) and Thonburi Energy Storage Systems (TESM) to open a battery production plant in 2019. BMW Group Thailand formed a partnership with Shell Thailand’s EV charger Shell Recharge to offer EV charging solutions that allow customers to charge their cars on the go at Shell’s flagship service station in 2021.

- Joint ventures (JVs) by automotive OEMs and new nontraditional players enter EV market. On the OEM side, Thai-Japan JV FOMM was the first automotive manufacturer to produce EVs in 2018. On the new nontraditional player side, Thai-based Arun Plus (a subsidiary of national oil & gas conglomerate PTT) has signed a JV with Taiwanese company Foxconn Technology (a subsidiary of electronics producer Hon Hai Precision) to build an EV production plant in 2021.

- Stake acquisition by new nontraditional players reflect investor interest. There have been a limited number of M&A transactions in the Thailand EV market in the past few years as players prefer partnerships and JVs. Only two players have pursued acquisition as a strategy, namely Banpu Power (acquired 21.5% shareholding in FOMM in 2019) and Energy Absolute (acquired stake in Absolute Assembly in 2021).

- Expansion plans by automotive OEMs and new nontraditional players to support EV market. BMW Group Thailand built a local high-voltage battery production plant in 2019, while new nontraditional player Energy Absolute built a lithium-ion battery (LIB) plant in 2021. Energy Absolute received a Green Loan from Asian Development Bank to increase the number of EV charging outlets to 1,000 by the end of 2021.

- A nascent EV startup ecosystem starts booming. According to investment research firm Tracxn, Thailand had 33 startups operating in the EV industry as of March 2022, ranging from electric rental platforms and EV manufacturing to EV charging stations. A few startups have entered the electric two-wheeler (2W) space for EV manufacturing, namely Edison Motors, Deco Green Energy, and i-Motor, launching their EV models in 2016, 2018, and 2020, respectively.

4 FUNDAMENTAL CHALLENGES

ADL has identified four key challenges that the Thailand government must address to internalize the electrification trend and transform itself quickly into an eco-friendly growth engine for the automotive sector. The four challenges are: (1) limited role in LIB supply chain, (2) limited strategic push for charging infrastructure, (3) limited potential of export market base given Thailand’s internal combustion and local content regulation, and (4) cautiousness of Japanese players.

1. Limited role in LIB supply chain

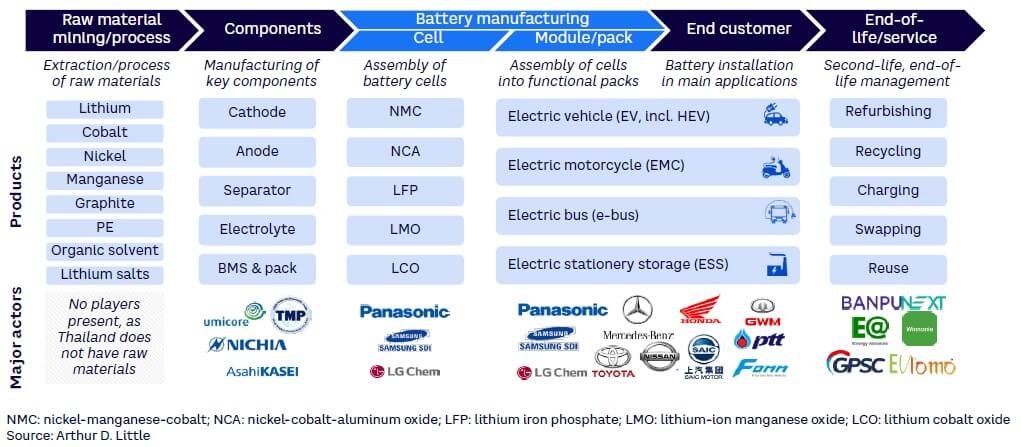

- Raw material plays a key role. The most significant process in the EV supply chain is the upstream stage, dealing with raw materials (lithium, cobalt, manganese, graphite, and nickel) and specialty chemicals used for production of LIB cells. As EV demand picks up, we need a lot more nickel, lithium, and cobalt across the globe and external dependence poses a high level of supply risk and an eventual cost impact.

- Limited mineral reserve for LIB. Thailand does not have any significant sources of LIB active material. This implies that the country will mainly be an assembly engine of producing models and packs from imported cells, implying a low local value addition and thereby limited localization. Moreover, a lack of such raw material may limit Thailand’s potential of attracting investment in high-end technology.

2. Limited strategic push for charging infrastructure

- Data for building public charging. The location of charger and type depends upon various factors, such as user behavior, utilization, location of charger, and time spent by typical user. Currently, no system exists for capturing such data points, which can aid in the decision making of setting up public chargers.

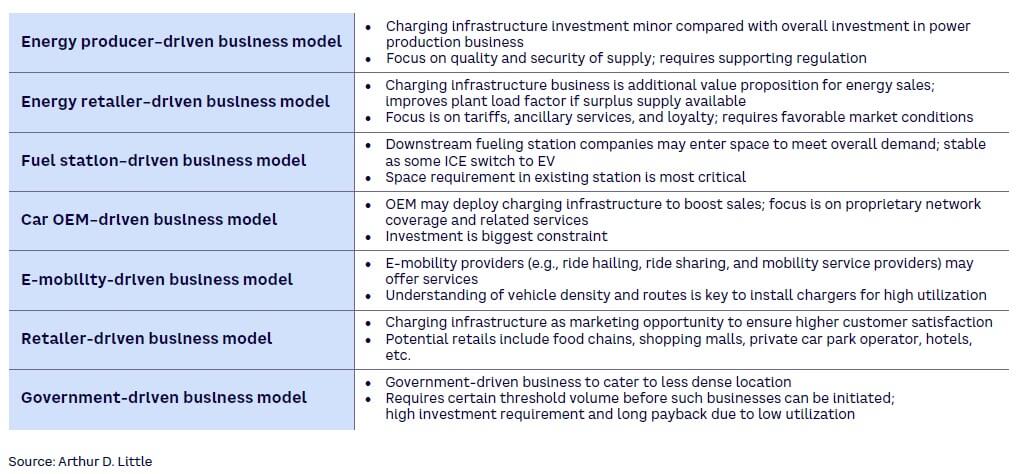

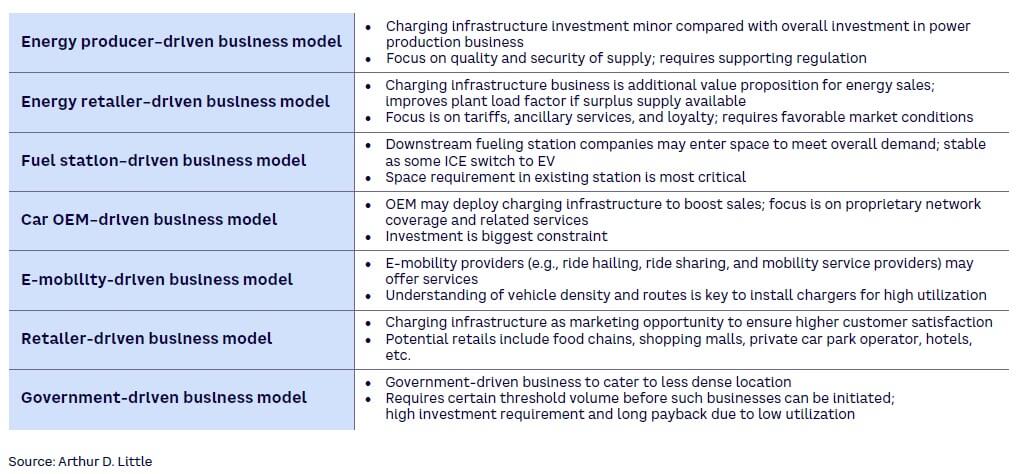

- Determine viable business model. The Thailand government has not recommended or endorsed any particular business model for charging infrastructure. The government and other related players in the EV charging market must explore which business models are more viable within the country’s local market conditions.

- Show financier the business case. The government should work closely with local authorities to identify high-density locations through vehicle data when presenting a viable business case to investors so that the charging operator has the necessary funds for the initial period of low or negative returns. Besides public-private participation, other options should be considered, such as avenues of green financing and allowing private investors the option of early termination; in which case, regulators can step in with residual financing.

3. Limited potential for export market

Close to 55% of the automotive production units are exported with Australia (17%), Japan (12%), China (11%), Vietnam (8%), and Philippines (7%) being the most significant, according to ADL analysis. However, such countries may not continue to attract EV products from Thailand in light of local content regulations and so forth; thus, Thailand’s priority should be to develop its own local EV supply chain.

4. Cautiousness of Japanese players

The role of Japanese OEMs cannot be denied in developing Thailand as an automotive hub, accounting for 80%-90% of automotive production, domestic sales, and export, according to ADL analysis. However, EV as a priority area for many Japanese OEMs is still low, as they believe in a more gradual transition from the ICE powertrain to the electric powertrain.

THAILAND’S READINESS FOR ELECTRIC MOBILITY

The Report provides an overview of the key results of ADL’s Global Electric Mobility Readiness Index (GEMRIX) 2022 edition,[1] focusing on the analysis of Thailand, which is categorized as an Emerging EV Market, alongside the US, Japan, and UAE with a score between 40 and 60. From this analysis, ADL sees immense potential for the Thailand EV market, given the strong push by the government, the presence of players across the EV ecosystem, and Thailand’s ambition to internalize the electrification trend. Based on the current market situation and expected future movements, we believe that the Thai government will most likely miss its 1.123 million ZEVs target by 2030. Below are some key recommendations for Thailand to achieve its EV dream — from a demand creation and supply development perspective.

Recommendations for the ecosystem

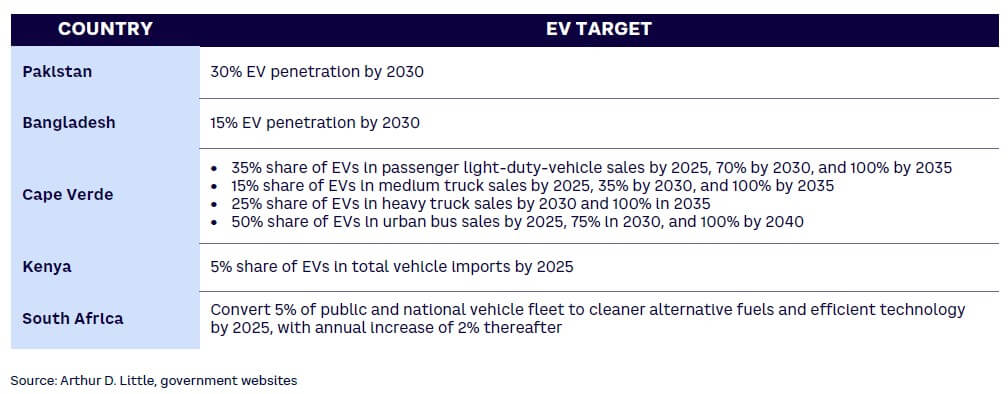

To create demand and incentivize adoption, increasing customer awareness of the switch from ICE to EV is crucial since customers currently lack knowledge regarding EVs. Secondly, the government can encourage adoption of EVs among B2B and B2B2C users through operational incentives, such as the cost of charging and dedicated parking lanes. Lastly, Thailand can also act as an export hub for Chinese OEMs to countries that lack a strong presence of supply chain but have announced EV policy targets to increase the demand.

Supply development is another approach the Thai government should consider. To support development, the country should work toward depending less on mass market Japanese OEMs and focusing instead on other OEMs, especially from China, which are more proactive in the EV space. Battery options are also a critical consideration; thus, the government should focus on exploring alternative battery options to localize production more fully. Lastly, the power industry can play an important role in supply development, since it should ensure that the energy grid is carefully planned to support the EV charging infrastructure and minimize incidents.

1

CURRENT SITUATION OF EVs IN THAILAND

Thailand is a key automotive hub in the SEA region. Often referred to as the “Automotive Hub of Asia,” Thailand is aiming to make the necessary transition toward the new global electrification trend. Doing so will allow the country to continue to attract foreign investment, which would move into areas of decarbonization of the transport sector, as well as contribute toward combatting air pollution. Despite various measures offered by the Thailand government, EV adoption rates are low. In this chapter, we discuss various factors behind low EV adoption, ranging from customer behavior, limited choice of EV models, unfavorable macroeconomics, and the absence of a charging infrastructure. We also focus on the factors necessitating the push toward EV adoption and identify reasons for the current low rate.

THE GENERAL PICTURE

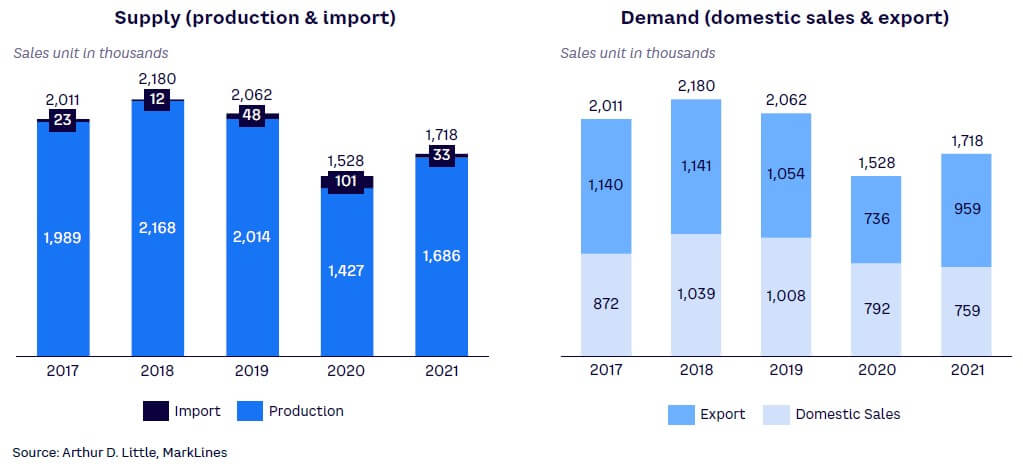

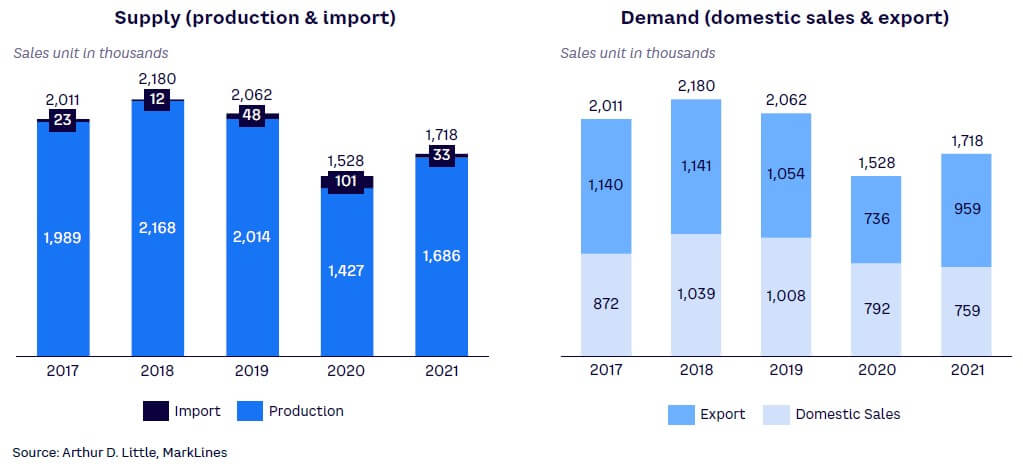

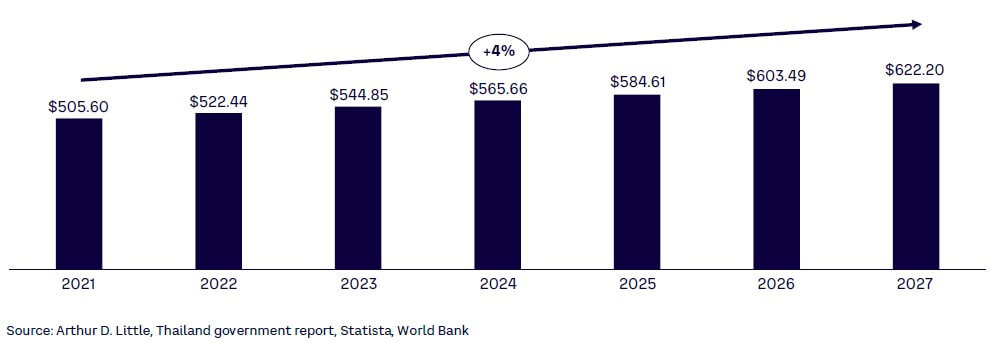

The Thailand automotive industry has been growing significantly over the past 55 years. It has contributed to 10% of the nation’s GDP with more than 759K vehicle units sold in 2021. This success has led the country to become the biggest automotive manufacturer in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the 10th largest car producer in the world. As the Automotive Hub of Asia, Thailand continuously positions itself as the next-generation automotive manufacturer with a higher value-added manufacture and environmental protection policy. Last year, Thailand produced 1,686K vehicles and imported 32K vehicles, of which 959K units were exports and 759K units were domestic sales (see Figure 1).

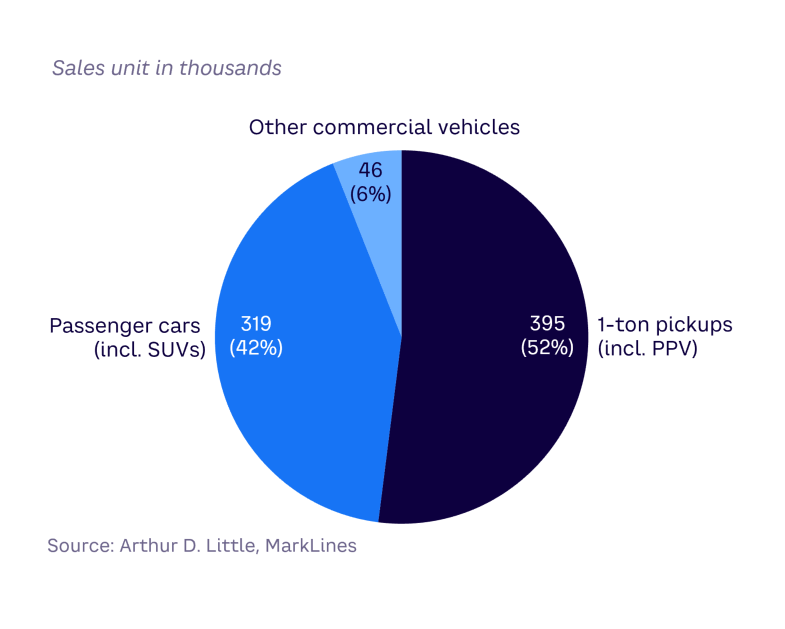

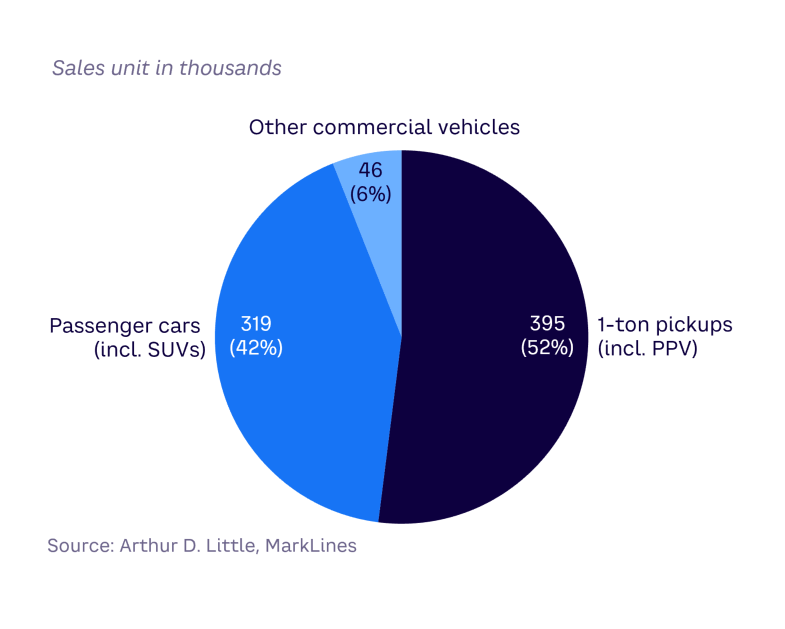

As shown in Figure 2, however, the industry is dominated by 1-ton pickups (including pickup passenger vehicles [PPVs]) with a market share of 52%, followed by passenger cars, including sport utility vehicles (SUVs) at 42%, and other commercial vehicles (6%). Owing to the macroeconomic outlook due to the growing urbanization rate and increasing income per capita, automotive continues to be one of the fastest-growing industries in Thailand.

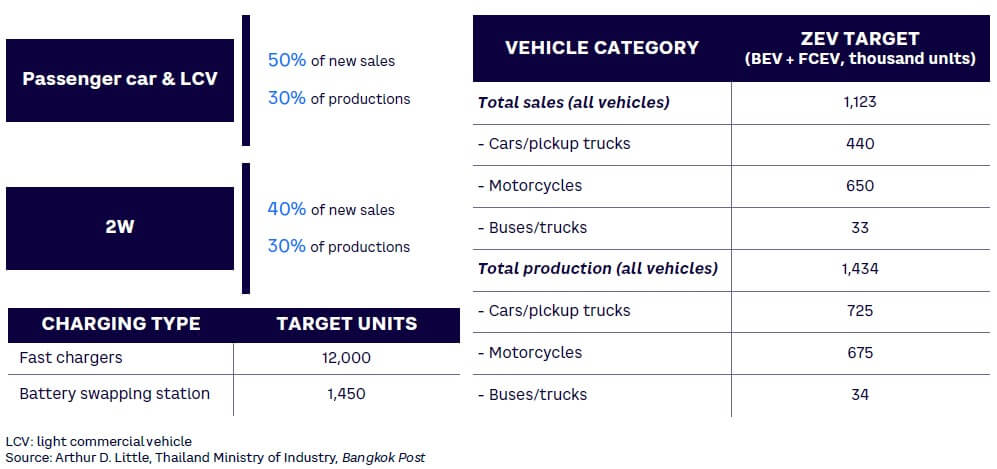

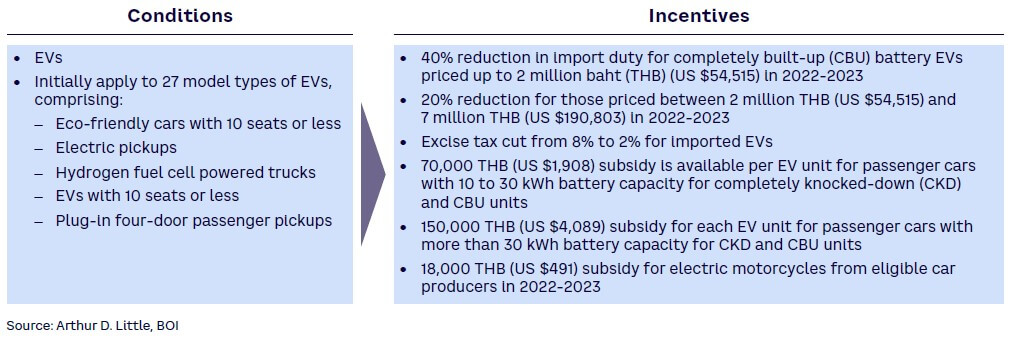

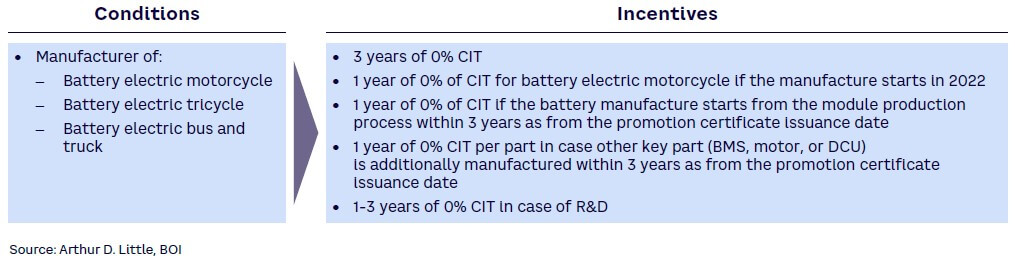

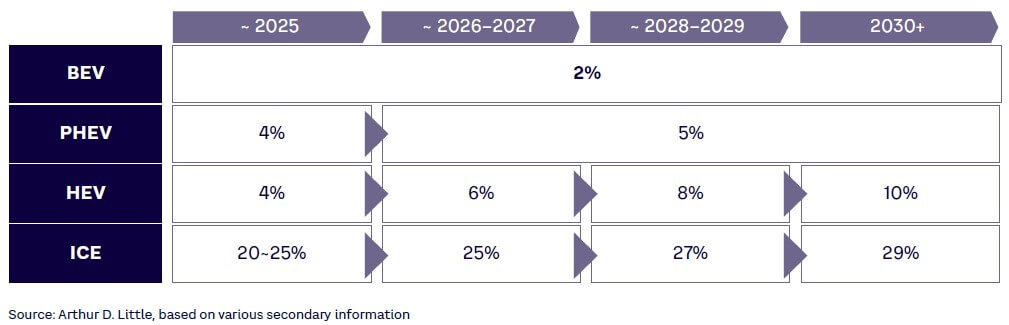

Electrification is a rising global trend with estimates by Bloomberg projecting 40 million EV sales per year by 2030 — a 20% stock share. Consequently, Thailand sees a promising opportunity in EV. This directly impacts future investment in the automotive space, which would be governed by carbon neutrality and sustainability norms. Thus, the Thailand government is aggressively pushing for the electrification of vehicles via various policies for EVs and xEVs (hybrid EVs [HEVs], plug-in hybrid EVs [PHEVs]) — see Figures 3a-3d. The government has set an aggressive ZEV target with its 30@30 vision, where ZEVs comprise BEVs and FCEVs — see Figure 4. As per this target, 30% of production in passenger cars and light commercial vehicles (LCVs) as well as 2Ws should be ZEV by 2030. In addition, the 30@30 electrification policy also states that all vehicles used by government agencies and public fleets produced in Thailand must be ZEVs. Such a bold policy stems from fact that the Thai government has committed to a carbon neutrality target by 2050 and net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2065. Since the transport and logistics sector contributes 29% to emissions, it’s a key area to prioritize for decarbonization and air cleanliness.

JOB CREATION & INVESTMENT

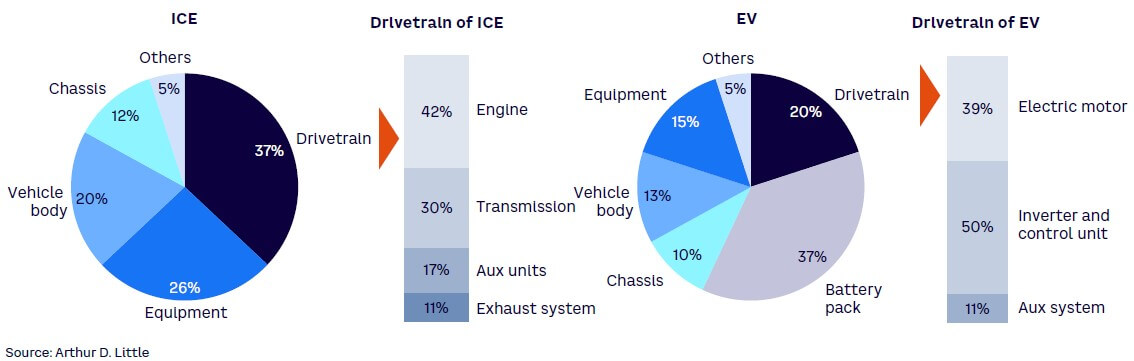

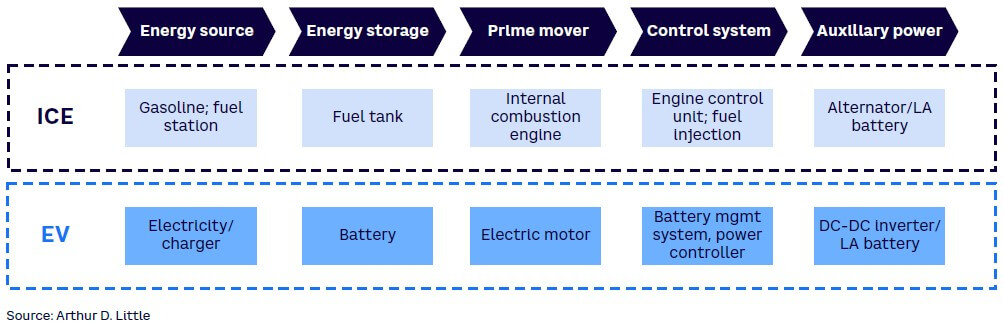

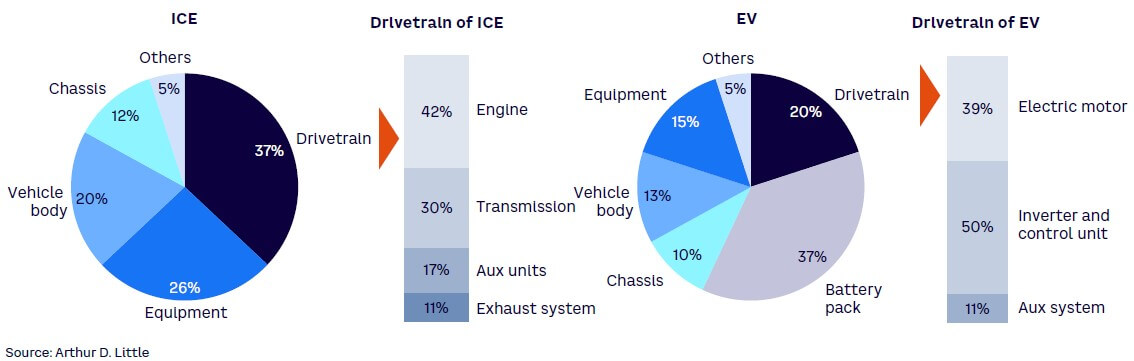

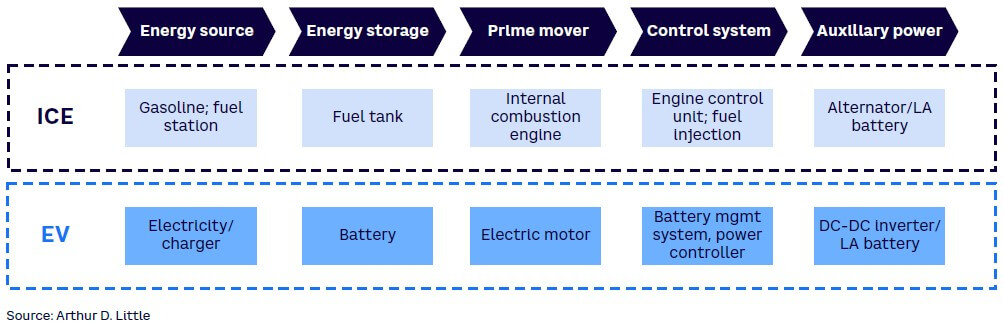

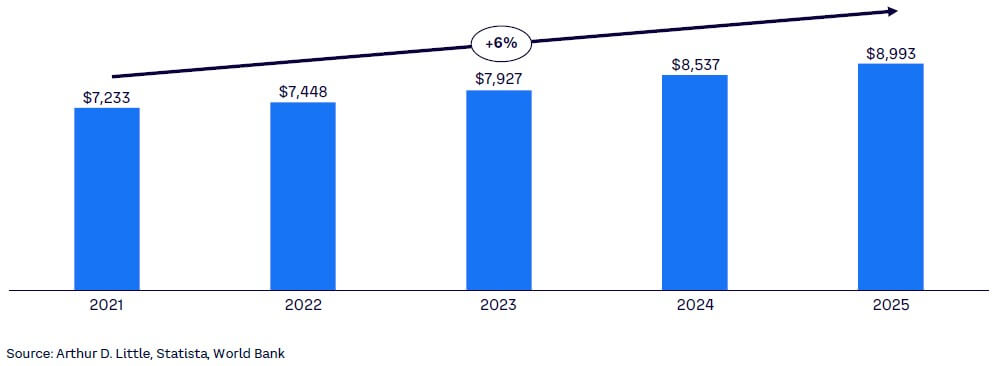

Since its beginning, Thailand’s automotive industry has been a significant contributor to the rising employment rate. Some experts believe that EV penetration will generate 1.3 million new employment opportunities in Thailand by 2035. As building a typical EV requires workers to have a technical skill set different from building an ICE vehicle, evident from the difference in cost breakdown of EVs versus ICEs (see Figure 5) and the replacement of key components (see Figure 6), there will be a growing demand for training the existent labor force and/or upgrading existing capabilities. Establishing an EV ecosystem is not only critical to achieve this target but also greatly impacts other industries, such as battery manufacturing, component developing, and technology services. Therefore, the government should work with the automotive industry to craft the future of e-mobility. With the advent of EV development, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow (US $19.4 billion in 2021) would increase in battery development, manufacturing, and recycling being the most critical investment areas.

CARBON NEUTRALITY TARGET & SAFE AIR

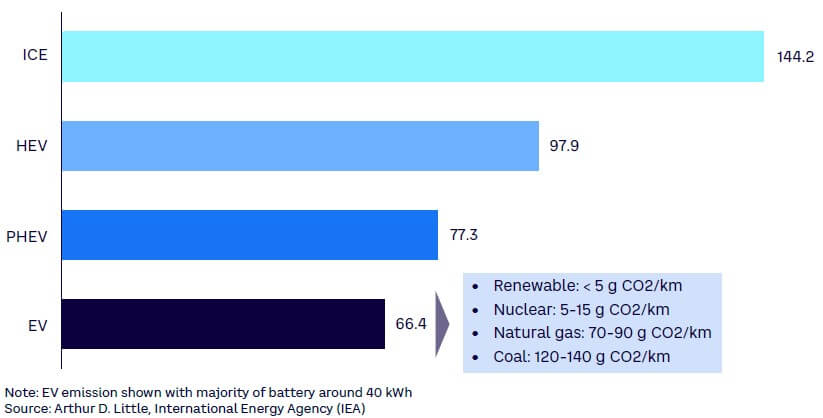

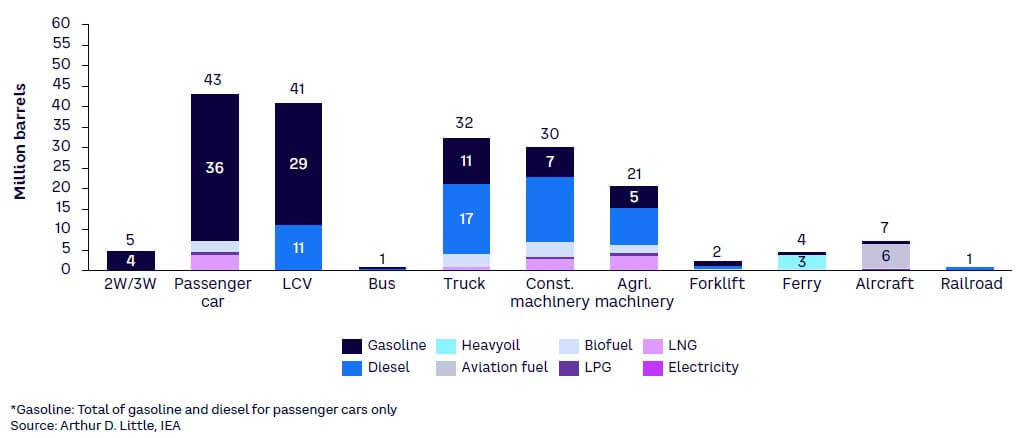

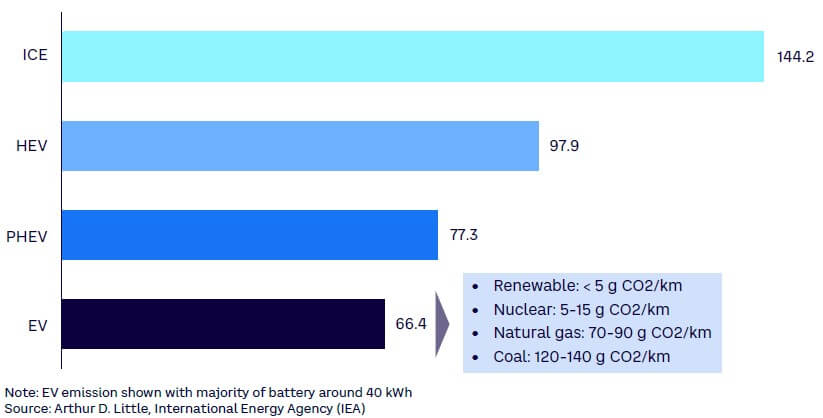

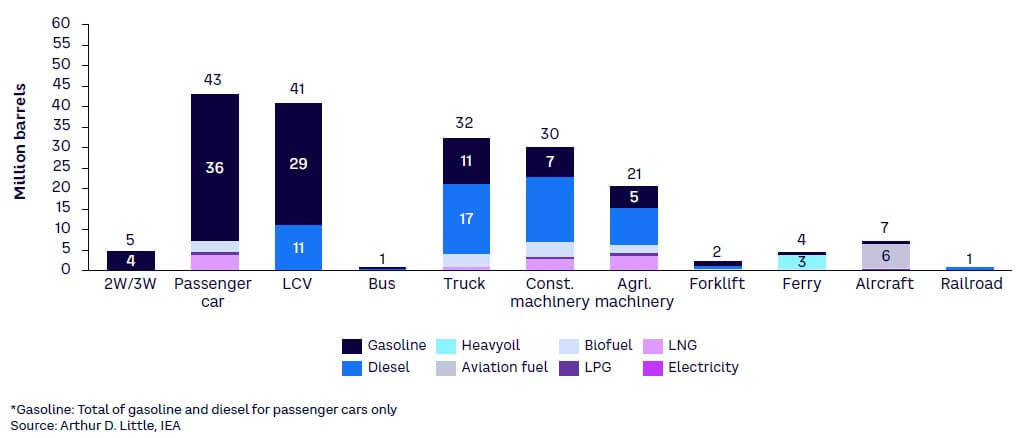

Thailand emits close to 250 million tons (Mt) of CO2 per year and has formulated the National Energy Plan (NEP) framework to achieve transformational change to clean energy systems with the goal of becoming a carbon neutral country by 2050. With 280 million vehicles on the road, road transport makes up to 90% of all energy consumption in the SEA region. Buying an EV contributes to net emission reduction as measured in grams CO2 per kilometer (g CO2/km) — see Figure 7 — with emission from EVs dependent on the source of energy for charging infrastructure. Through the increased use of renewables, as the Thai government is targeting the renewable energy (RE) share to be 30% of the power mix by 2030, EV emission is expected to further decline. Such an initiative would contribute toward addressing the issue of air pollution, a key area of concern for Thailand, as pollution contributed to 29,000 deaths in Thailand in 2021, according to Greenpeace SEA. A shift toward zero-emissions EVs will contribute to cleaner transport, directly helping reduce air pollution problems.

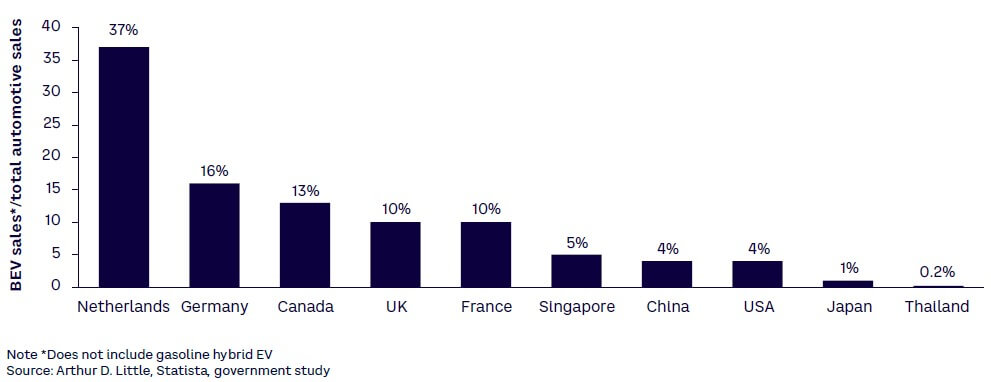

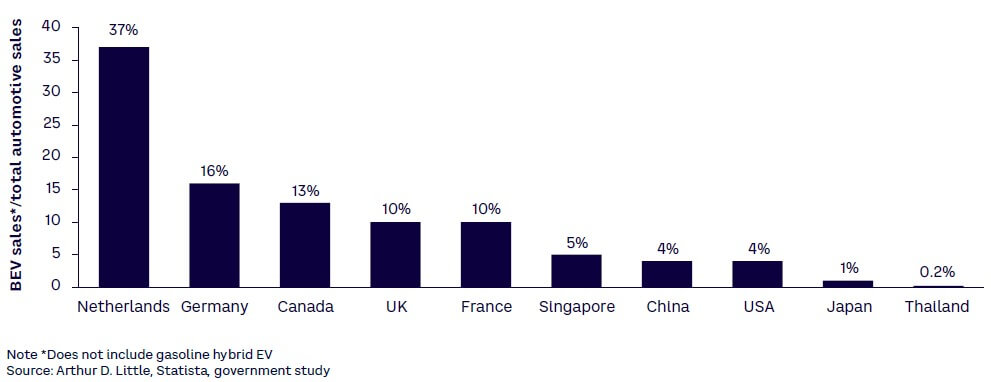

However, Thailand still has a low EV adoption rate compared to other countries despite the government offering demand-side and supply-side incentives. The EV adoption rate in Thailand is just 0.2%, which lags far behind many European countries with the rate around 10% and other benchmarks, such as Canada, US, China, and Singapore (see Figure 8).

FACTORS BEHIND LOW EV ADOPTION

There are many aspects that have contributed to Thailand’s low EV adoption rate. The following are some of the most essential:

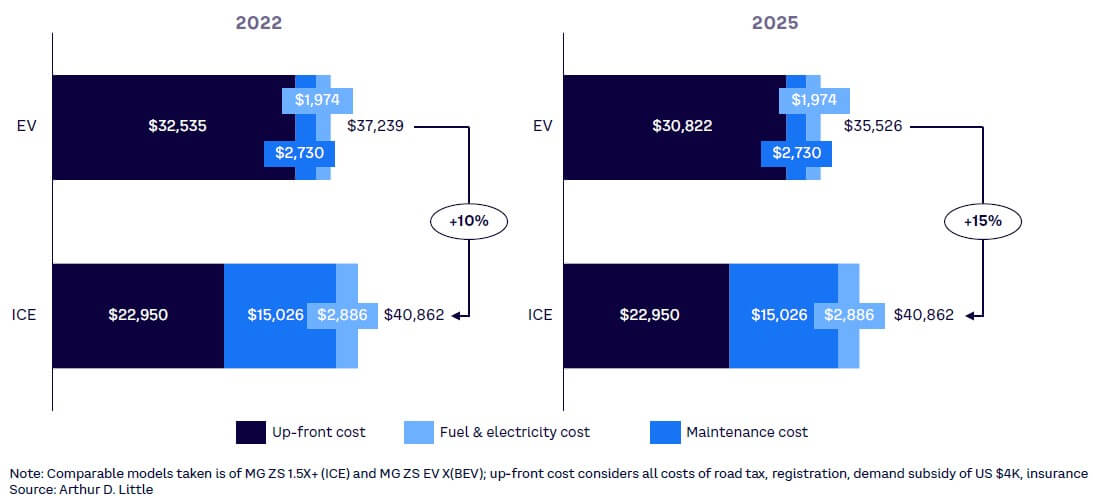

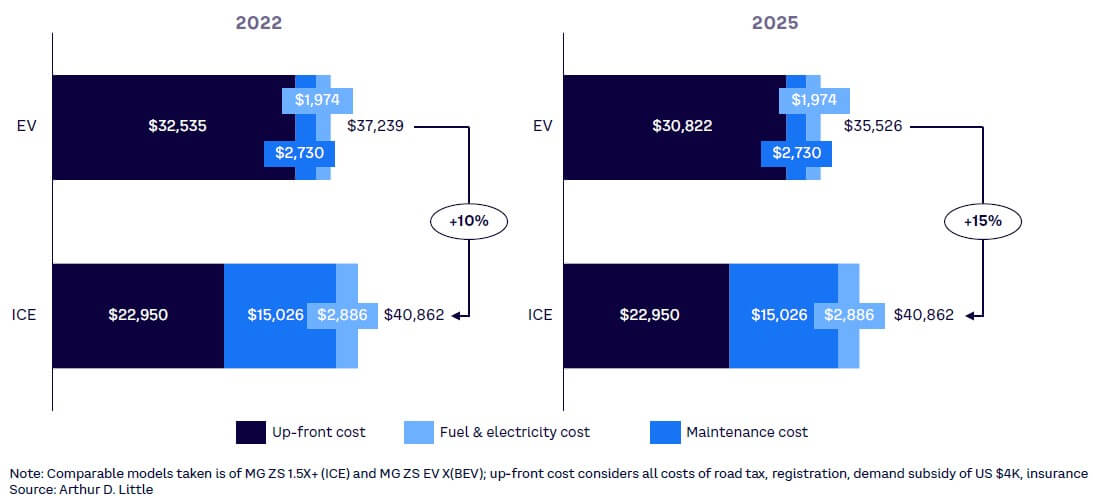

- Minimum daily distance is insufficient for TCO; greater preference on initial cost. EVs today are more expensive than their ICE counterparts given rising battery cost and lack of sufficient scale. For instance, the cheapest EV variant of the MG four-seat PC (with a government subsidy of US $4K) costs US $22,856 (ex-showroom), while its ICE variant of MG PC costs start at US $13,219 (ex-showroom). This expensive pricing has pushed consumers away from EVs because there are a wide range of cheaper ICE vehicles available.

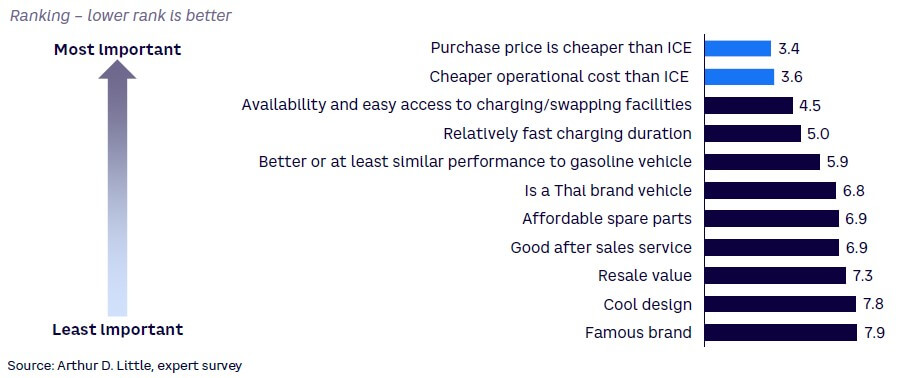

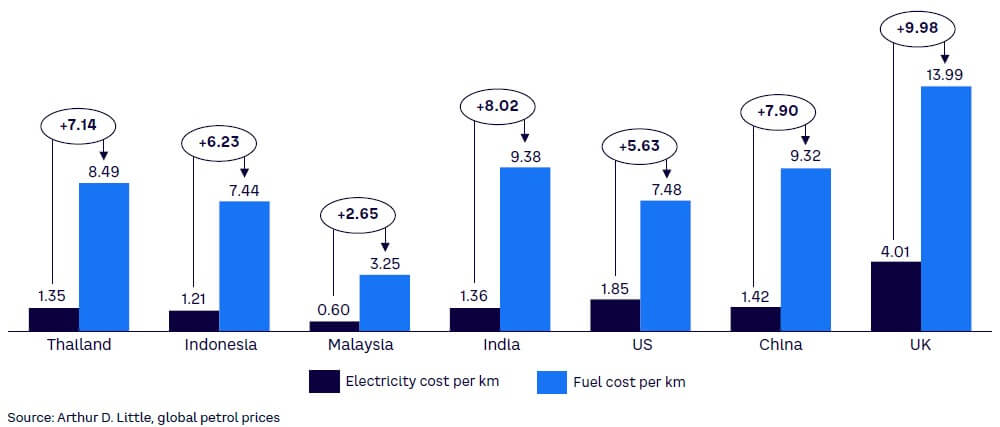

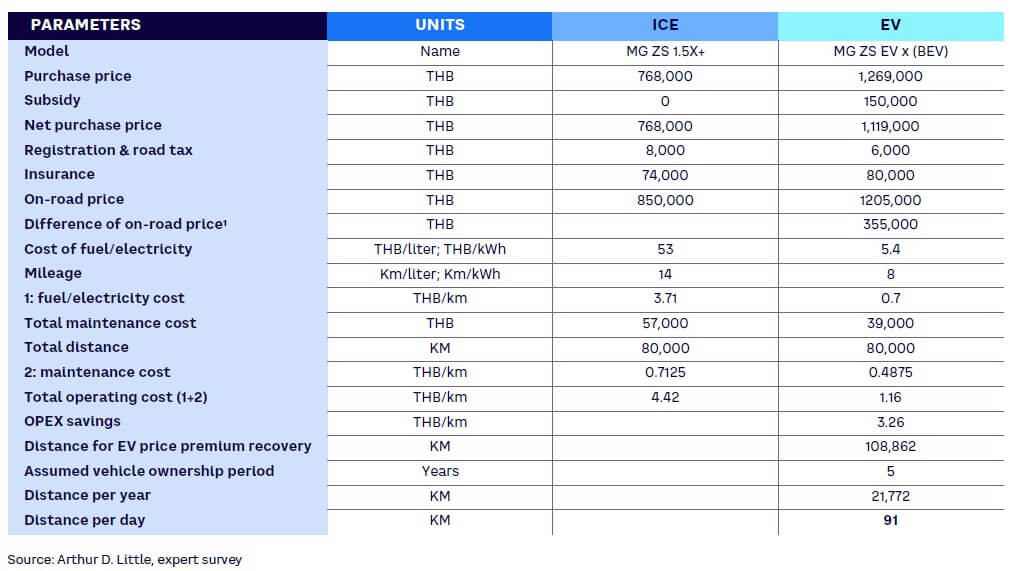

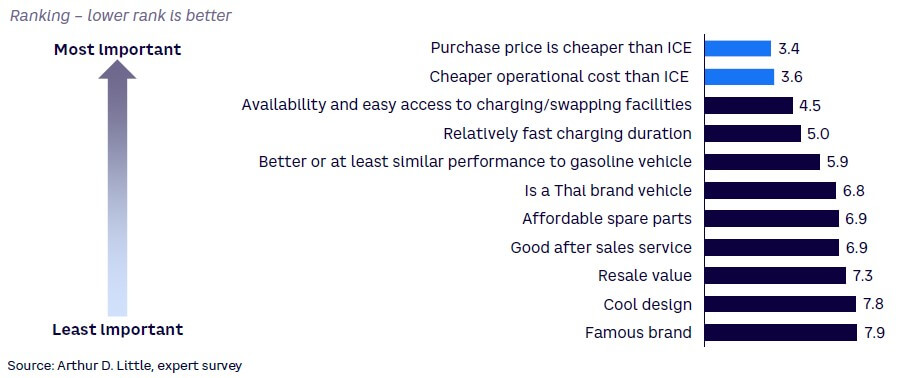

TCO remains the top concern for adoption of EVs in SEA, whereas other developed markets may incentivize EV adoption from the point of view of environmental friendliness. From a TCO perspective, the minimum distance that a typical four-wheeler (4W) EV driver needs to drive to overcome the EV premium via savings from low maintenance and fuel costs is 91 km per day (see Figure 9), compared to the typical driving distance of 43 km per day in the Bangkok area and 39 km per day in the provincial area. This is a key reason why EV adoption is low. Despite EV fuel costs being 20% of ICE and maintenance costs being 25% of ICE, consumers today still prefer ICE over EV because decisions are based on initial cost rather than TCO analysis (see Figure 10).

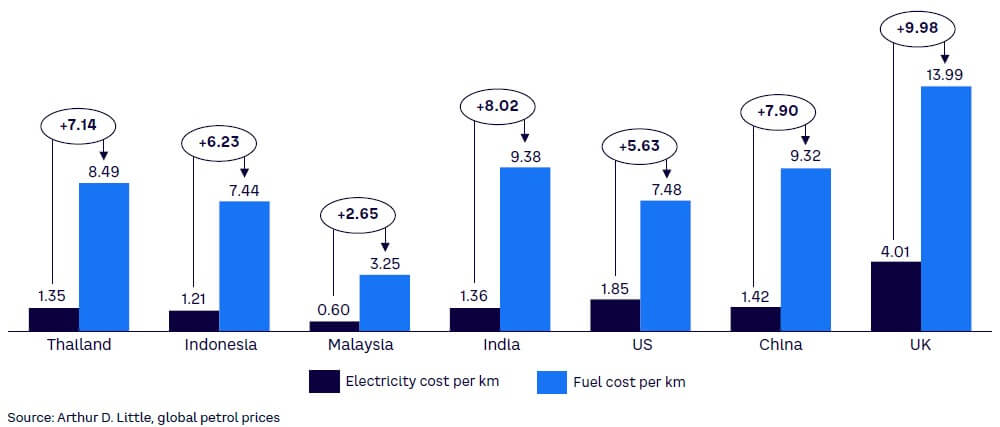

Even though EVs have an advantage over ICE vehicles via lower running cost, the trigger to consider EV is more pronounced if the difference between fuel and electricity is larger, as these are the costs consumers face on a daily basis. Recently, Indian consumers have started considering EV more openly as the price gap between fuel and electricity cost has widened (see Figure 11). Previously, the price gap was similar to markets such as Thailand and China but with recent oil price movements, the gap has increased. For Thailand, the price gap of electricity versus fuel cost is still less than US 8 cents, which may widen as Thailand subsidizes the cost of EV charging with increased RE integration.

- Customers prefer more choice; limited availability of EV models. In 2021, there were a limited number of EV models available in Thailand, with just 19 in the market, compared to 184 ICE models (see Figure 12). This translates into a ratio of 9.7 ICE models to 1 EV, with countries such as China having a 2.2:1 ratio of ICE to EV. OEM model availability naturally favors higher EV adoption because consumers want more choices to fit their lifestyle and budget; hence, they are hesitant to buy an EV as the primary mode of personal transport. In addition, there is a huge price gap between the cheapest EV car model (US $22,856, post subsidy) and the cheapest ICE car model (US $9,073). Thus, EVs are not attractive compared to ICEs in terms of model availability and pricing.

Figure 12. Number of Light Vehicle models* in Asia, June 2022 - Unfavorable macro factors hinder growth of EV usage. The global shortage of semiconductor chips and the COVID-19 pandemic are two key macroeconomic factors that have impeded the pace of EV adoption in Thailand. On the supply side, OEMs are unable to launch innovative EV models designed for the Thailand market due to the global semiconductor chip shortage, thereby lowering the priority of EVs due to its current market size. On the demand side, inflation has been increasing over the last few years except for 2020 (COVID year) and a reduction in purchasing power due to the negative short-term economic impact of COVID-19 have affected demand sentiments.

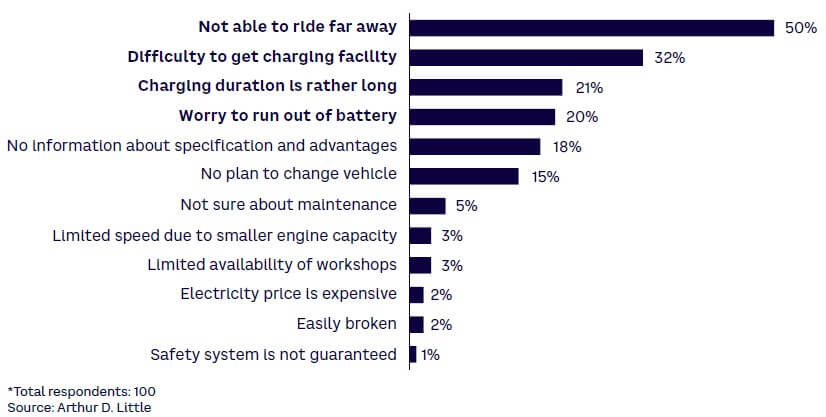

- Critical mass of charging infrastructure impedes EV adoption. Thailand’s public EV charging infrastructure (693 charging stations as of September 2021) is far behind other Asian countries that are making efforts to establish a strong EV ecosystem; China has 1.4 million charging stations, South Korea has 105K, and India has 21K. Even though the government has taken numerous measures to prioritize EV charging development in Thailand through the offering of charging operator’s tax benefits, ISO certification removal, and soft loan provision, Thailand still has a limited charging infrastructure. Initiatives are needed to support the development of a commercially viable business case for a charging infrastructure by promoting certain business models and providing relevant data input for a credible business case for financiers and investors. A target setting of 12K fast chargers and 1,450 swapping stations by 2030 is insufficient. Such concerns are making customers hesitant to use EVs, leading to low EV adoption.

Given the factors above, Thailand’s EV adoption rate is quite low. At the end of this Report, we offer recommendations that may yield a significant outcome for the Thailand EV industry in upcoming years.

2

REGULATORY PUSH & MARKET MOVEMENTS SPARK OPTIMISM

Thailand holds a favorable position to drive the future of the EV industry. As the government sets a clear agenda to achieve its ZEV target of 1.123 million ZEVs and carbon neutrality target by 2050, it has provided attractive incentives for the supply side, the demand side, and the EV charging infrastructure. Moreover, there are dynamic market movements among automotive OEMs, related EV peers, new nontraditional players, and startups. In this chapter, we discuss several initiatives taking place in the Thailand market, which we broadly categorized as regulatory push and market movements. We focus on these activities as a source of optimism regarding movements in the right direction toward realizing the EV dream.

The world is going green, and Thailand is no exception. To push toward its carbon neutrality target, Thailand sees EV as a game changer. Several key initiatives have been rolled out in the Thailand market to achieve the EV push. For example, in February 2022, the government released new incentives for the EV industry as part of its ambitious plan to become a manufacturing base for cleaner vehicles in SEA. Various automotive OEMs, such as Volvo, Mercedes-Benz, SAIC, and Great Wall Motor (GWM), have announced entry to the EV market with new product launches, while several Thailand companies, such as PTT, GPSC, Energy Absolute, and Banpu Power, are playing an active role in the EV value chain.

REGULATORY PUSH

The Thailand National EV Policy Committee has introduced a roadmap as a framework for Thailand’s EV development from 2021–2035 with the aim to develop a well-established supply chain for manufacturing EV and for building the technological capacity for modern mobility. The roadmap focuses on the entire value chain from upstream activities of battery manufacturing, components, and EV production to downstream activities — from the charging infrastructure to related safety standards — to facilitate comprehensive implementation.

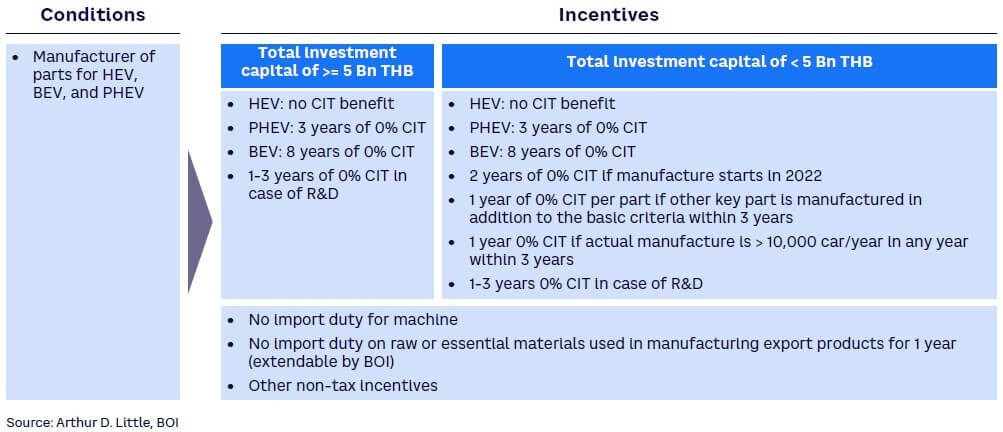

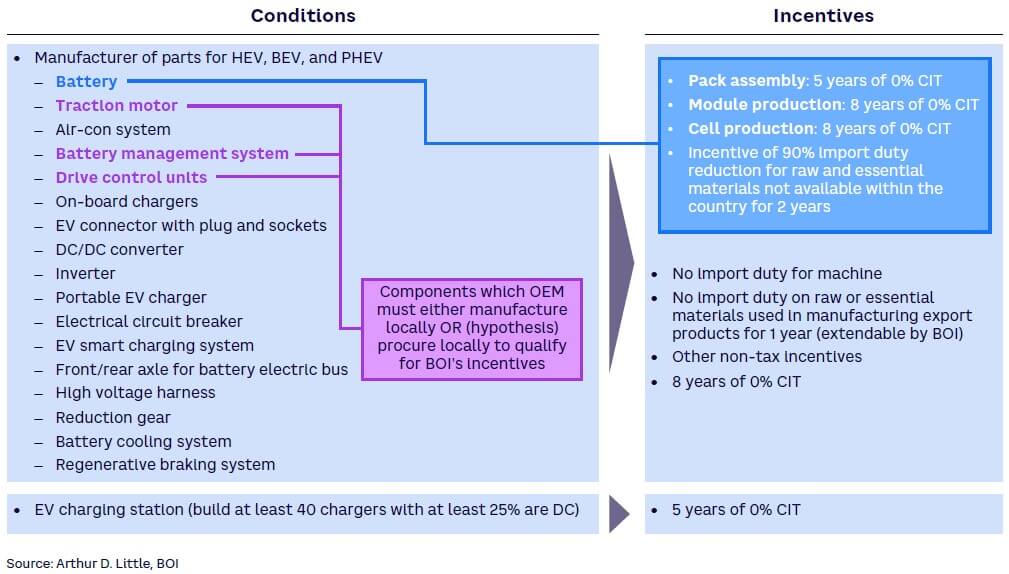

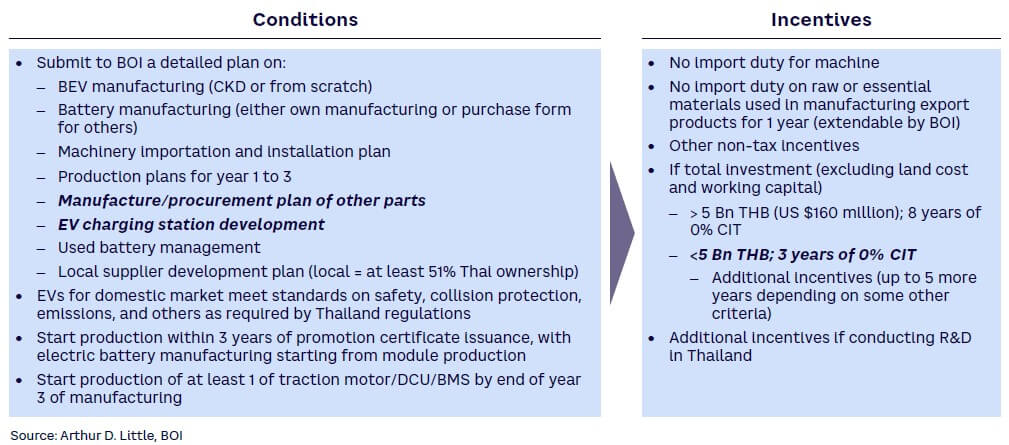

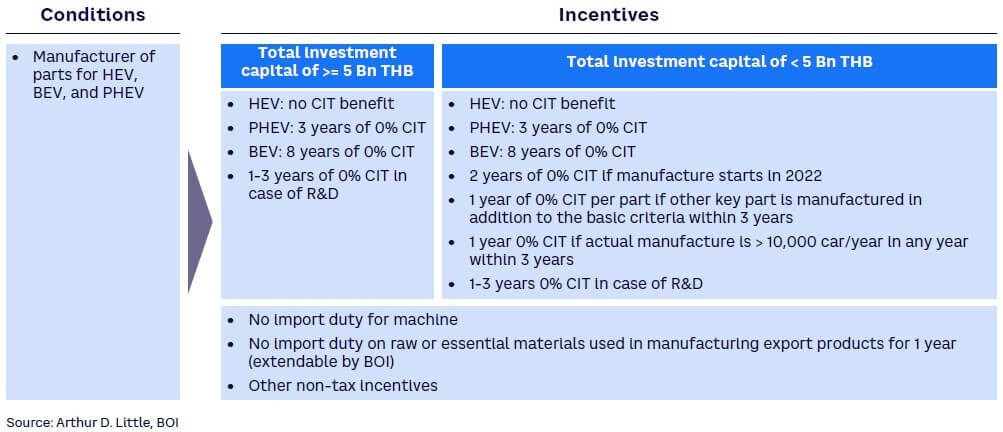

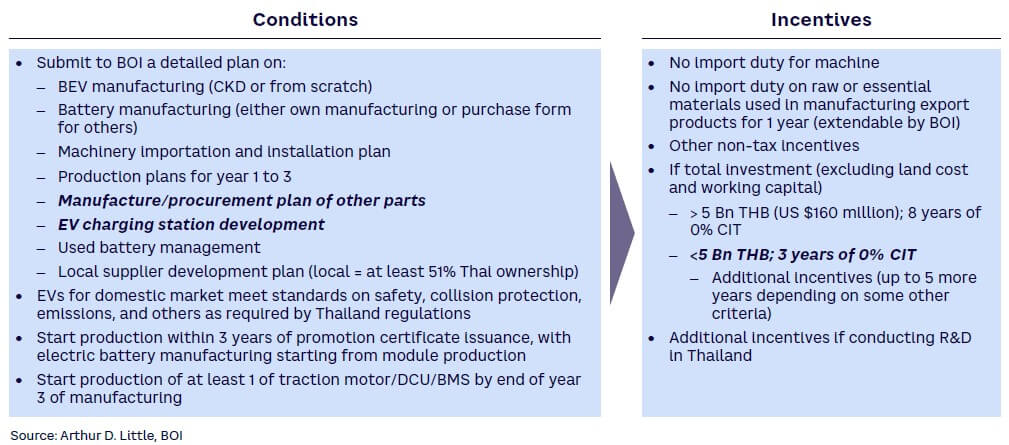

As discussed earlier, the government has set a target of 30% production of ZEV vehicles (BEV and FCEV) by 2030. Thailand’s BOI offers various incentives for EV manufactures, such as zero import duty for machine/raw materials and CIT exemption for three to eight years (see Figure 13).

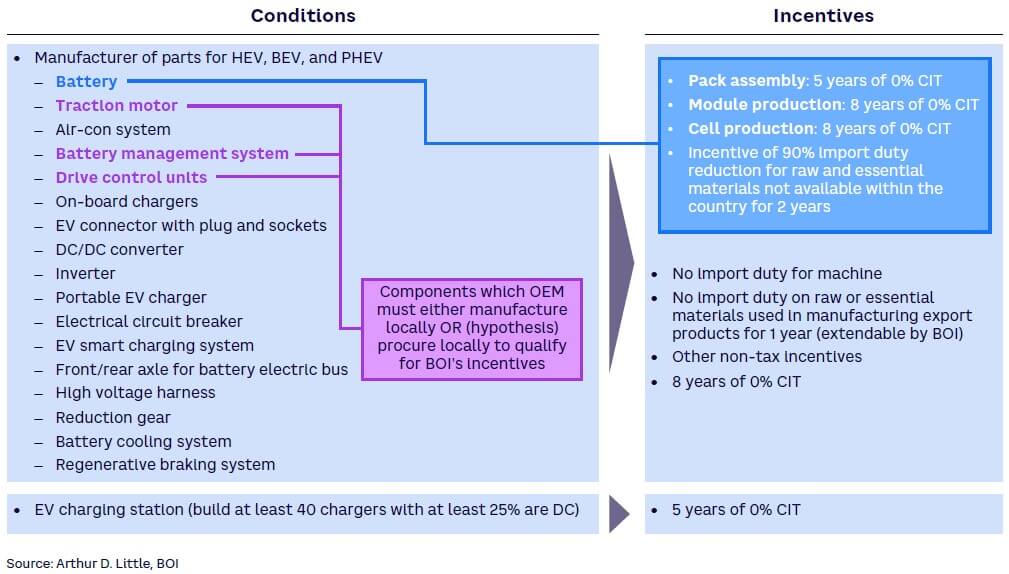

Within three years from the issuance date of the investment promotion certificate, EV manufacturers are required to source the battery module and one of three components (i.e., traction motor, DCU, BMS) locally to qualify for the incentives. Moreover, Thailand’s BOI is also pushing for CIT exemptions for BEV-related components (refer back to Figure 3d in Chapter 1) to provide more comprehensive and integrated incentives to develop the EV industry. Such incentives would fuel OEMs to enter battery and module production in the next 12-24 months.

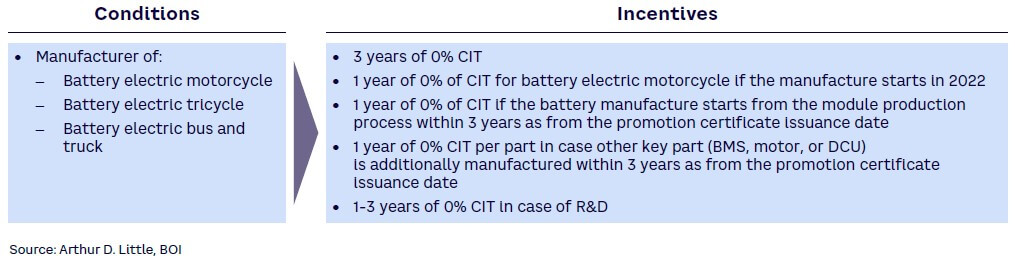

On the demand side, in February 2022, the government announced its latest incentive package, including a reduction in import duty for CBU BEVs, an excise tax cut for imported EVs, and an EV subsidy for passenger cars (refer back to Figure 3a in Chapter 1). Up until the end of 2022, a subsidy of US $90.4 million is sanctioned, while a subsidy of US $1.2 billion is expected until end of 2025. In addition, the government offers a five-year CIT exemption for EV charging operators that build at least 40 chargers (with at least 25% as DC chargers), given that the National EV Policy Committee set targets for the development of charging stations (12K charging stations for EV cars and pickup trucks and 1,450 battery exchange stations for EV bikes by 2030) to support e-mobility and EV infrastructure nationwide. These are indications that EV adoption will increase in the coming years. Finally, the government’s promotion of EV adoption is also evident from preferential tax treatment (see Figure 14).

We believe the regulatory push will encourage EV adoption, given the comprehensive set of incentives that support the overall EV ecosystem with a balanced focus toward supply-side and demand-side incentives.

MARKET MOVEMENTS

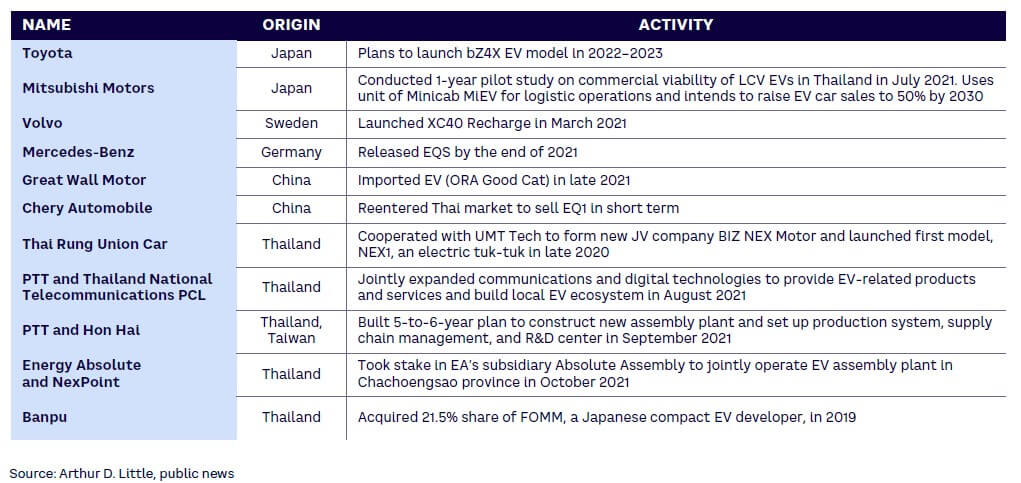

Overall, automotive OEMs have been gearing up for EV production after the Thailand government proposed attractive incentives to manufacture EVs. New nontraditional players such as PTT, Energy Absolute, and Banpu Power have entered the EV market through JVs and acquisitions to internalize the rising EV trend. In addition, we observe that both domestic and foreign investors have increased their stakes in battery manufacturing and EV charging stations.

New product launches serve Thailand consumers

Automotive OEMs are well prepared to prioritize EV portfolios reflecting product launches. Both local OEMs and foreign OEMs are actively launching new EV models in the market. Thailand manufacturers such as Mine Mobility (Energy Absolute’s EV business) and Takano Auto, respectively, launched the first homegrown BEV (MINE SPA1) and electrified mini pickup truck (TTE 500) in 2020. In addition, European OEMs such as Volvo and Mercedes-Benz are enhancing their manufacturing footprints in Thailand by ramping up e-mobility through releasing an electric SUV (XC40 Recharge) in early 2021 and introducing an EV (EQS) and PHEV (S 580 e) in late 2021. Chinese OEMs have also prioritized their EV push in the Thailand market with the launch by SAIC, GWM, and Chery Automotive via an EV (MG EP) and PHEV (NEW MG HS) in 2020, imported an EV (ORA Good Cat) in late 2021, and put Chery’s new EV on the market in late 2022. Seeing strong growth in the EV market, SAIC plans to launch another EV model (NEW MG ZS EV) in 2022 and expects to launch another product in 2024.

Japanese OEMs, on the other hand, are less bullish with EV launches. Instead, their focus has been on xEVs with Honda and Toyota launching an HEV (City Hatchback e:HEV) and EV (bZ4X EV) in late 2021 and 2022, respectively, while Mitsubishi conducted a one-year pilot study for LCVs in late 2021. Overall, market movements by Japanese OEMs do not appear to be promising in the EV domain, while other nontraditional and Chinese OEMs are leading market movements from an EV perspective. As nontraditional and Chinese players intensify their efforts in the EV domain, the adoption rate is expected to increase in coming years.

Partnerships to strengthen EV ecosystem

Cooperation among leading OEMs, power-generation developers, and component producers is essential to help complete the entire EV ecosystem. Mercedes-Benz Thailand partnered with TAAP and TESM to open a battery production plant in 2019. Thai public company GPSC announced its collaboration with nine Thai enterprises to develop prototype common battery packs and a battery-swapping system in April 2021. BMW Group Thailand formed a partnership with Shell Thailand’s EV charger Shell Recharge to offer EV charging solutions that allow customers to charge their cars on the go at Shell’s flagship service station in 2021. Moreover, BMW Group Thailand partnered with Polytechnology, Greenlots Central Group, and AP (Thailand) to introduce ChargeNow as Thailand’s first public charging station for any xEV car brands. US-based EVLOMO partnered with PTT Oil and Retail Business PLC (PTT OR) to launch an EV charging station in 2021. EVLOMO is also setting up a swapping center in partnership with PTT OR and Toyota Tsusho, with EVLOMO focusing on investing in the battery-swapping network, PTT OR providing data relevant to local market conditions, and Toyota Tsusho providing battery packs. Such collaborations can help fill any gaps in battery manufacturing and the overall charging infrastructure for Thailand’s EV ecosystem.

Using JV to enter EV market

Thailand has emerged as an attractive market for EVs for both automotive OEMs and new nontraditional players to produce EVs and batteries. On the automotive OEM side, Thai-Japan JV FOMM was the first automotive manufacturer to produce EVs in 2018 with the world’s smallest class four-seater EV. Thailand OEM Thai Rung collaborated with mass transit company Urban Mobility Tech (UMT) to establish JV BIZ NEX Motor to launch an electric tuk-tuk (NEX1) in late 2020. Meanwhile, Thai-Chinese JV SAIC Motor-CP, a manufacturer and distributor of MG cars, invested US $9 million to produce batteries for EVs and manufacture EVs in Thailand in 2023. In addition, Chinese OEM established a JV with Thailand manufacturing company Sammitr Group to produce a six-wheel EV truck by 2024.

On the new nontraditional player side, a Thai-listed company Chai Watana Tannery Group formed a JV with Thai transportation service company Sakun C Innovation to launch the world’s first EV aluminum bus in August 2020. Moreover, Thailand company Arun Plus (a subsidiary of national oil & gas conglomerate PTT) signed a JV with Taiwanese company Foxconn Technology (a subsidiary of electronics producer Hon Hai Precision) to build an EV production plan in 2021. Arun Plus has also signed a strategic collaboration with CATL to accelerate a fully integrated EV supply chain with ASEAN. In addition, Arun Plus is partnering with various 2W and e-bus players to study electrification in those types of transportation modes.

Arun Plus, PTT OR is targeting to set up 300 stations by 2022/2023 with Onion Mobility and around 1,000 swapping centers with Arun Plus, offering a battery-swapping service in the Cambodia market, learning of which would be transferred to the Thailand market. PTT also has plans to learn from its collaboration with companies such as EVLOMO to eventually launch its own Swap & Go center with the target of 2,000 stations in next 12-24 months.

With regard to battery development, US company EVLOMO established a JV with Thai industrial park operator Rojana Industrial Park to build an EV battery production plant in the Chonburi province in 2021. These JVs emphasize the attractiveness of the Thailand EV market to both foreign and domestic investors.

Acquisitions by new nontraditional players reflect investor interest

There have been a limited number of M&A transactions in the Thailand EV market in the past few years as players prefer partnerships and JVs. Only two players have pursued acquisition as a strategy, namely Banpu Power and Energy Absolute. Banpu Power acquired 21.5% shareholding (US $20 million) in FOMM (Japan’s EV developer) to enter the EV market in 2019. Furthermore, it also purchased a 23% stake in Muvmi (e-tuktuk mobile app in Bangkok) and introduced BanpuNEXT EV Car Sharing for rental of FOMM EVs to the market in 2020. Energy Absolute and NEX Point acquired a stake in Absolute Assembly to operate the EV assembly plant in the Chachoengsao province in October 2021.

Expansion plans to support EV market

OEMs are backward- or forward-integrating in other areas of the EV ecosystem as well, such as battery and charging infrastructure for larger ecosystem play. For instance, BMW Group Thailand built a local high-voltage battery production plant in the Chonburi province in 2019. New nontraditional players such as Energy Absolute and GPSC built a LIB plant in the Chachoengsao province and began operations in June 2021, establishing a semi-solid battery to manufacture G-Cell batteries in July 2021, respectively. Regarding EV chargers, Energy Absolute received a Green Loan from Asian Development Bank to increase the number of EV charging outlets to 1,000 by in the next few years; meanwhile, ABB won a contract by Thailand’s Provincial Electricity Authority to install over 120 EV fast chargers across the country by the end of 2021, but a slight delay has been seen. In addition, Thai charging operator Sharge Management aims to add 600 night stations (charge-at-home) with 2,000-4,000 chargers in 2022. As a result, these business expansions will help enhance EV support areas in the EV market.

Nascent EV startup ecosystem starts booming

As mentioned earlier, Thailand had 33 startups operating in the EV industry as of March 2022, ranging from electric rental platforms and EV manufacturing to EV charging stations. Given our market scan, we find that the startup ecosystem is slowly flourishing with most startups focusing on EV manufacturing and/or the charging infrastructure. A few startups have entered the electric 2W space for EV manufacturing, namely Edison Motors, Deco Green Energy, and i-Motor. Edison Motors came to the market in 2016 to develop various models for electric scooters (e.g., Edison Volta S, Volta E, Volta Carry) at a range of 150 km. Deco Green Energy, founded in 2018, engaged in the production and distribution of electric scooters and bicycles and developed both 2Ws and three-wheelers (3Ws) for personal transportation, agricultural use, and delivery. In 2020, i-Motor produced various models for electric 2Ws (e.g., Neo, 3E series, Evo, Servo) at different ranges (80 km, 85 km, 90 km), catering to different customer preferences and requirements. Moreover, i-Motor has its own mobile app, Yapp, for consumers to search vital information, such as battery swap stations and insurance purchasing.

A handful of startups are also providing EV rentals (e.g., Haup, SCOOTA). Haup, established in 2016, is an app-based platform providing multi-category EV (e.g., electric car, electric kick scooter) rental services for short-term and long-term usage. Besides Haup, SCOOTA, founded in 2018, is an app-based rental platform focusing on electric kick scooters and operating in select cities of Thailand. The presence of such players allows consumers to test out and try out the electric 2W, building the necessary confidence in an Emerging EV Market like Thailand.

Regarding EV charging stations, Forth entered the market in 2017 to manufacture EV charging terminals, offering Smarger (personal charger, maximum output power of 3.68 kW) and EV Net (commercial charger, maximum output power of 7.4 kW) to serve global automakers. In the meantime, another startup named PromptCharge focused on the niche market to provide EV chargers at home (output power of 3.6 kW, 7.2 kW, or 22 kW). Evolt Technology, which provides charger supply, platform, and software management, joined Banpu NEXT to expand the EV charging station platform in 2021. Such EV charging operators help improve the EV charging infrastructure.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Regulatory and market movements are promising, given ADL’s market scan and analysis. Automotive OEMs are entering the EV market via new product launches, partnerships, and JVs, while new nontraditional players choose market strategy via JV, M&A, and business expansion. Startups that focus on electric 2Ws and EV charging stations also play a critical role in the EV value chain. All three types of players — automotive OEMs, new nontraditional players, and startups — have been gearing up their EV strategy and readiness and providing a sense of optimism about the EV industry in Thailand in the short-to-medium term. We will return to the impact of regulatory push and market movements at the end of this Report.

3

KEY CHALLENGES IN ENABLING THAILAND AS EV HUB

As the 10th biggest car producer in the world and the largest in ASEAN, Thailand’s role in the ICE industry cannot be denied. With the advent of EVs in ASEAN and the rest of the world, the Thailand automotive industry has an opportunity to generate huge future revenue in the areas of EV component manufacturing, power storage technology, charger devices, smart electronics, and connectivity software. The Thailand government wants its local market to be a hub for ZEV as well as for xEV production by 2035, five years earlier than previously planned. The government push toward sustainability in the mobility sector can be seen through a series of supply-side and demand-side policies. Moreover, as highlighted earlier in this Report, the government is committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, with biofuel and electrification being a key policy instrument to reduce emissions from the transport sector. Thailand’s transport and logistics sector contributes close to 29% of total emission (based on ADL analysis in 2019); hence, this would be a key sector for decarbonization.

As shown in Figure 15, the passenger car segment will contribute the most to emission reduction, since it’s the largest vehicle segment. The public transport infrastructure and network will also have to be prioritized for achieving decarbonization of the transport sector. Complete transformation of the vehicle fleet in the areas of 2W, 3W, passenger car, bus, and LCV (to an extent possible) would be needed, along with the development of a public EV fast-charging network. In addition, the government must prioritize biofuel usage in the larger commercial vehicle segment, where electrification is difficult due to requirements of higher range and mileage without impacting the vehicle payload. This is needed to minimize the cannibalization effect, which may occur if both biofuel and electrification target the same vehicle segment.

The focus of this chapter is not to discuss regulatory issues but rather market-based challenges that the government must tackle, since they could impact realizing the dream of Thailand as an EV hub.

4 FUNDAMENTAL CHALLENGES

ADL has identified four key challenges that the Thailand government must address to internalize the electrification trend and transform itself quickly into an eco-friendly growth engine for the automotive sector. The four challenges are: (1) limited role in LIB supply chain, (2) limited strategic push for charging infrastructure, (3) limited potential of export market base given Thailand’s internal combustion and local content regulation, and (4) cautiousness of Japanese players.

1. Limited role in LIB supply chain

Given that LIB plays an important role in EV manufacturing, the lack of a significant source of raw material for LIB cells in Thailand poses challenges for the country.

Raw materials play key role

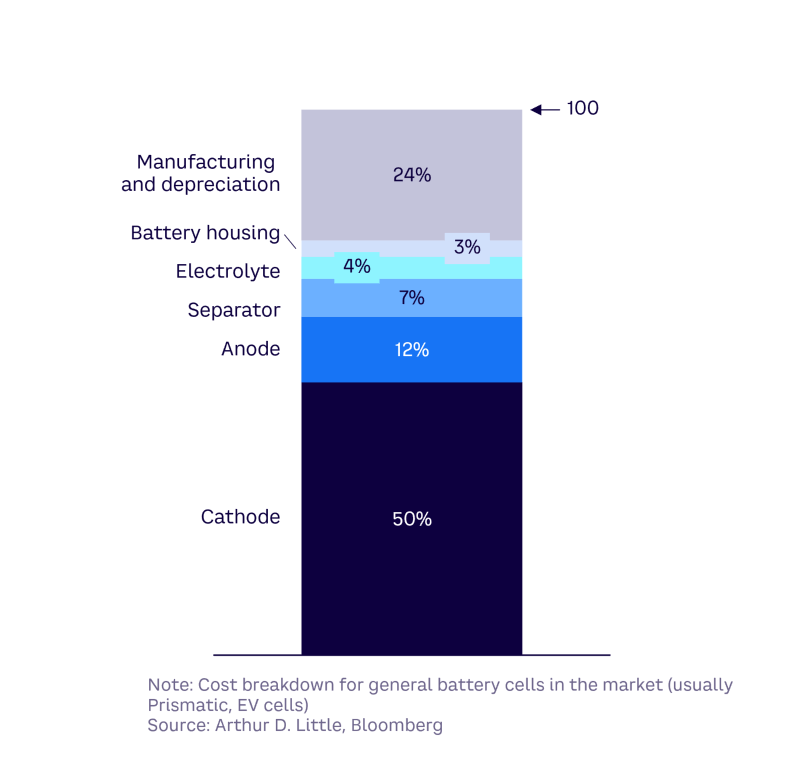

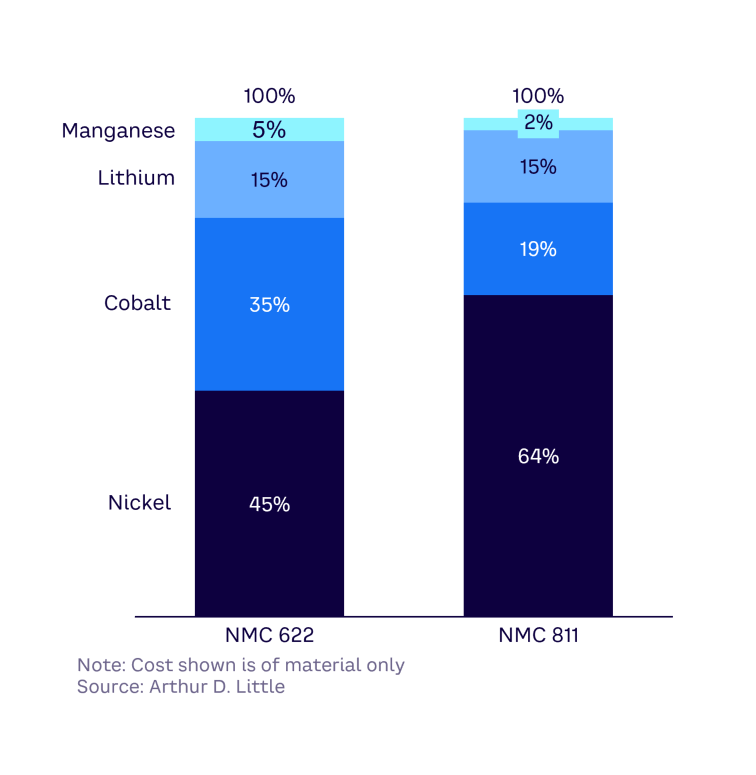

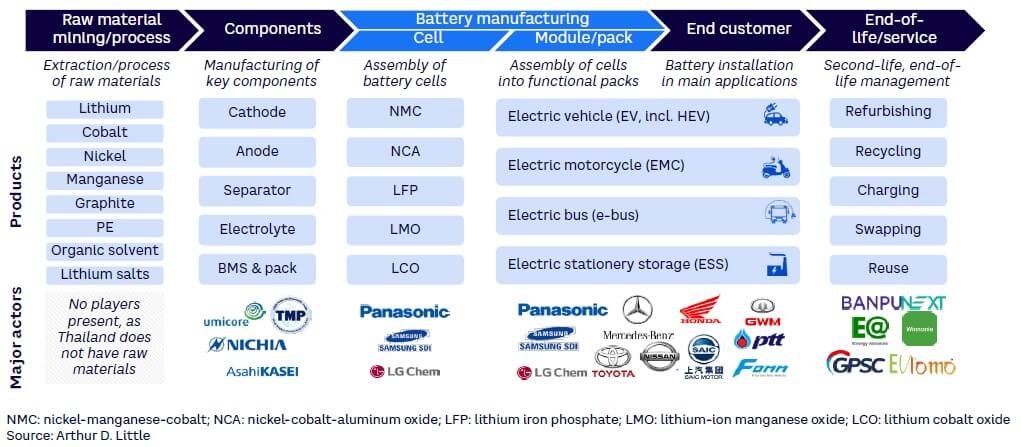

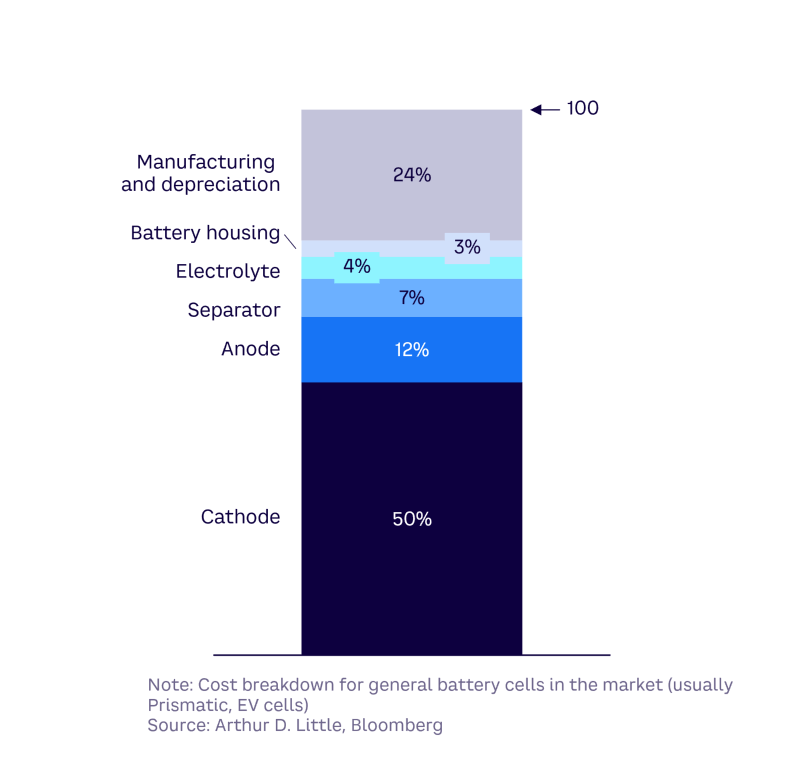

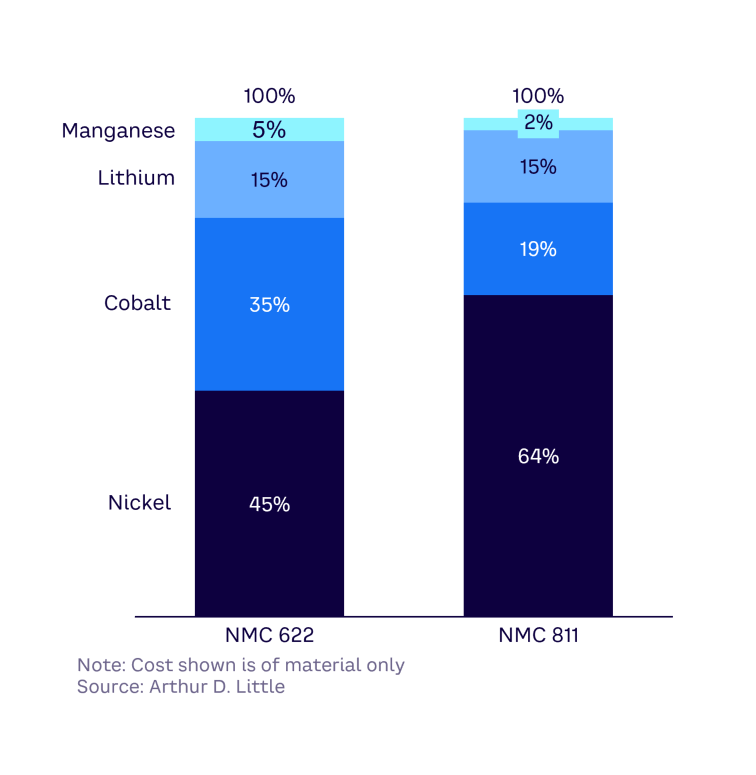

The EV supply chain can broadly be classified into different stages, as shown in Figure 16. The most significant process is the upstream stage, dealing with the raw materials and specialty chemicals used for production of LIB cells. These are the active materials (e.g., lithium, cobalt, manganese, graphite, and nickel) used for the production of cathode and anode. Cathode and anode determine the overall cell chemistry and EV performance, such as driving range and charging, accounting for 51% and 12%, respectively, of LIB cell cost of goods sold (COGS) — see Figure 17. Based on different cell types (NMC 622, NMC 811, LFP), the cost impact of different materials can be quite significant, as shown in Figure 18.

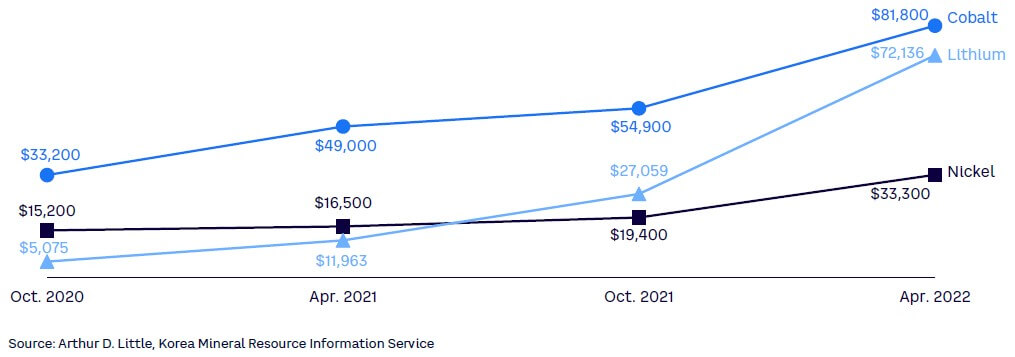

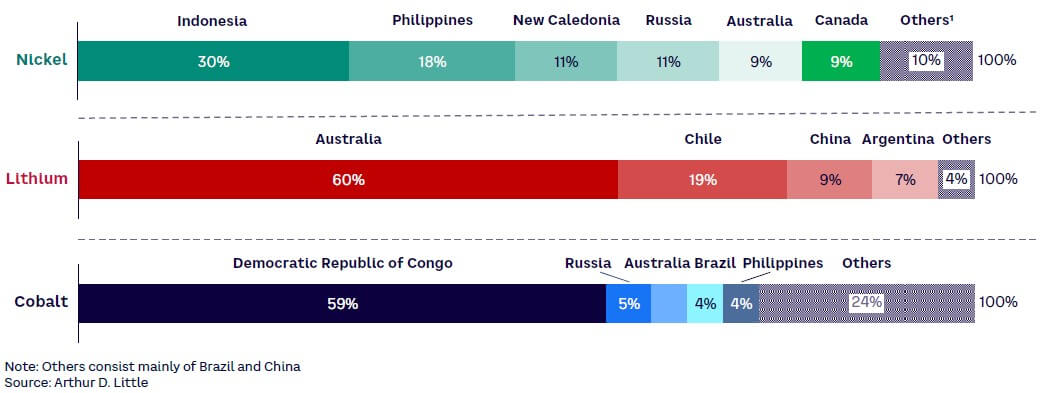

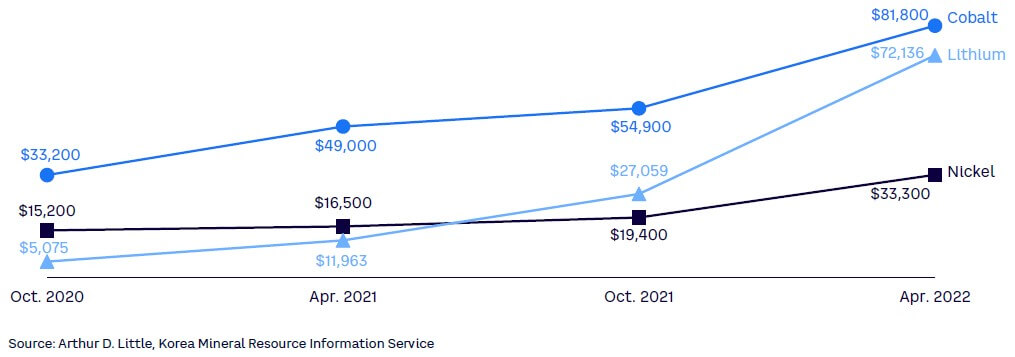

The price of active material has moved significantly since the start of 2021 with the price of lithium having moved 700%, cobalt by 70%, and nickel by 100% (see Figure 19). Given the demand projection for EV by the International Energy Association (IEA), the world will require a 40-fold increase in production lithium and nickel and more than 20 times cobalt, copper, and graphite (anode) by 2040, compared to 2020. This implies that a lot more nickel, lithium, and cobalt would be needed across the globe, and external dependence poses a high level of supply risk and an eventual cost impact.

Low mineral reserve for LIB cells

Thailand does not have any significant sources of LIB active material, as shown Figure 20. This implies that Thailand will mainly be an assembly engine of producing models and packs from imported cells, implying a low local value addition and thereby limited localization. Within its own vicinity, Thailand faces competition from Indonesia. According to Bloomberg, Indonesia holds the world’s largest nickel reserve and can offer the lowest cost of EV battery manufacturing among all Asian countries. According to ADL estimates, the cost can be 8% lower than China. Availability of LIB cell raw material is also an incentive for companies to set up a manufacturing facility in critical areas, since cell and power control units provide the biggest contribution to EVs as share of the vehicle bill of materials (BOM). In December 2020, Korean company LG Chem, one of largest EV battery suppliers committed to investing US $9.8 billion with a consortium of Indonesia state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to develop the local EV battery supply chain from upstream mining to downstream production. In April 2022, Chinese cell manufacturer CATL has also committed to an investment of US $6 billion together with the Indonesia government. Such moves have encouraged leading EV OEMs like Tesla to consider establishing an EV manufacturing plant in Indonesia. Investment in cell and battery packs, which contribute to 35%-50% of vehicle BOM, may offer markets like Indonesia better cost competitiveness. Hence, a lack of such raw material may limit Thailand’s potential of attracting investment in high-end technology.

2. Limited strategic push for charging infrastructure

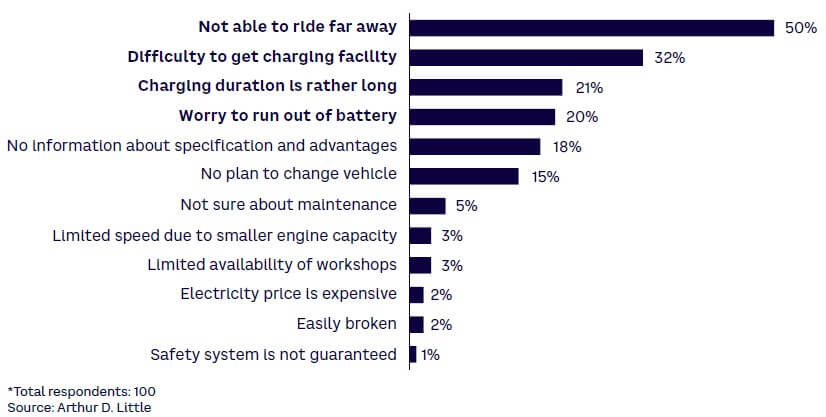

As of September 2021, there are 2,285 EV chargers (outlets) in Thailand with around 693 stations. Compared to the number of petrol pumps, this number is inadequate. Based on the recent ADL survey, close to 75% of respondents believe that public charging stations are not enough worldwide. As shown in Figure 21, the ADL survey revealed that some of the biggest hurdles for consumers to purchase EVs can be categorized around range anxiety, difficulty to access charging facility, charging duration, and fear of running out of battery. The Thailand government has announced a target of 2,200-2,400 DC charging stations by 2025 and 12,000 by 2030; however, as noted, there are only 693 stations (as of September 2021).

Lack of data for building charging stations

The location of charger and type depends upon various factors, such as user behavior, utilization, location of charger, and time spent by typical user. These must all be considered for the strategic deployment of EV chargers; otherwise, the EV market becomes a niche market. Currently, no system exists for capturing such data points, which can aid in the decision making of setting up public chargers. Moreover, the Thai government has not considered public-private participation yet in order to make projects work from a bankability perspective. Absence of safety standards for governing different public chargers is also a concern for many parking operators who fear leasing their space for EV charging in the case of any adverse impact of EVs catching fire.

Determine viable business model

The Thailand government has not recommended or endorsed any particular business model for the charging infrastructure. Besides typical charging infrastructure companies, other business models can exist (see Figure 22). The government and other related players in the EV charging market must explore which business models are more viable within Thailand local market conditions. This requires assessing types of EV segments, user charging patterns, and requirements. Additional revenue streams should also be identified, including advertisement, target marketing, and commission-based sales of product. This is important since the initial phase of overall EV adoption would be low; hence, operators need to rely on ancillary revenue streams.

Show financier the business case

The Thai government has taken various measures to prioritize EV charging development through tax benefits for the charging operator, removal of the ISO certification requirement, and provisions for a soft loan. Still, more concerted efforts are needed to present a viable business case. The profitability of charging stations and the payback period depend on utilization and physical infrastructure cost (e.g., land). The government should work closely with local authorities to identify high-density locations through vehicle data when presenting a viable business case to investors so that the charging operator has the necessary funds for the initial period of low or negative returns.

Besides public-private participation, other options should be considered, such as avenues of green financing and allowing private investors the option of early termination; in which case, regulators can step in with residual financing.

3. Limited potential of export market

Despite a population of only about 66 million, Thailand is the 10th largest automotive producer globally and the largest in SEA. This is primarily due to Thailand’s strategic location and its ability to export in nearby regions and markets. According to ADL analysis, close to 55% of the automotive production units are exported with Australia (17%), Japan (12%), China (11%), Vietnam (8%), and Philippines (7%) being the most significant. However, such countries may not continue to attract EV products from Thailand. For instance, countries such as Australia have a wide variety of LIB cell minerals, so there might be a possibility of imposing local content regulation. Similarly, Vietnam may prioritize development of its homegrown OEM, VinFast, as well as suppliers developing in the country to maximize scale. These factors will impact the EV market in Thailand. Thus, Thailand’s priority should be to identify new export frontiers.

These informal trade barriers are not new. Already, countries such as Indonesia and India have imposed local content requirements. Indonesia, for example, has introduced time-based local content regulation, which mandates a minimum value in different vehicle segments in a time-based manner (see Figure 23). Similarly, under its FAME 2 policy addendum, India has stated all parts except cells must be produced locally for products to continue to get a demand-side subsidy. Moreover, there are already expectations in the Indian market that cells have to be localized in the near future to ensure cost competitiveness and continue to meet the demand-side subsidy from the central government’s EV scheme.

In essence, to develop local supply chain capability, potential trade barriers can be imposed on Thailand-made EV products, which essentially limits the export potential of Thailand. This brings us to the key point that LIB cell and battery production is a capital-intensive process, and a key lever to reduce cost is to increase scale of production. Producing at an efficient scale is a significant enabler for cost optimization and, for Thailand in particular, the importance of this factor is more critical given the country doesn’t have a local mineral reserve impacting the overall cost of LIB cell and battery, which is close to 40%-50% of overall vehicle cost. In addition, the potential export market must also have the necessary charging infrastructure to continue to attract EV demand in a sustained manner. While countries such as Laos, Cambodia, and Philippines may be potential export destinations, their importance in terms of overall market is limited by its size and the pace of charging infrastructure development.

4. Cautiousness of Japanese players

The role of Japanese OEMs cannot be denied in developing Thailand as an automotive hub, accounting for 80%-90% of automotive production, domestic sales, and export. Toyota alone accounts for 38% of production, 41% domestic sales, and 37% of exports. The role of Japanese automotive players also impacts the overall auto component industry with Japanese-based companies contributing close to 50%-60% of overall revenue. Such a trend is evident given the Japanese philosophy of keiretsu, a traditional concept of the buyer and seller developing close collaboration.

Japanese OEMs’ lackluster attitude can be gauged from Figure 24, which shows Honda, Mitsubishi Motor, and Toyota announcing some initiatives but mostly in the xEV domain. Honda is launching a hybrid version of the City, while Mitsubishi Motor is conducting a study to assess the potential of EV in the logistics sector.

Japanese OEMs, given their investment in the ICE powertrain, is keener to prioritize alternate fuel technology. In January 2022, Toyota — along with Mazda Motor, Subaru, Yamaha, and Kawasaki Heavy Industries — announced a collaboration to explore the viability of alternative fuels for ICE engines, such as biofuel, hydrogen, and synthetic fuel.

EV as a priority area for many of the Japanese OEMs is still low, as they believe in a more gradual transition from the ICE powertrain to the electric powertrain via PHEV, hybrids, and then EV, factoring in that the immediate cleanup of a clean energy source is difficult. Such an approach has a knock-on effect on the supplier community as well with Japanese OEMs continuing to prioritize ICE production, leaving a lesser incentive for suppliers to initiate R&D in EV-related components. While for 30% of parts (by value) would be common, independent of ICE and EV, an area where Thailand has a natural cost advantage, there are areas of power control unit, thermal and battery management, sensors, motor, and controller where part producers in Thailand need to develop and prove its capability.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Thailand’s automotive capability and availability of a vast manufacturing base give it the ability to transform itself from an ICE hub to an EV hub. However, we believe that its realization depends on a concerted effort toward addressing the four challenges identified above. While the government is making the right move in terms of both supply-side and demand-side incentives, we believe focused efforts need to be taken to address the issue of Thailand’s limited position in the LIB supply chain, unleashing the charging infrastructure through actual business cases, identifying new export frontiers, and promoting new types of OEMs — traditional players from other countries as well as nontraditional counterparts (i.e., startups, technology players).

4

THAILAND ELECTRIC MOBILITY READINESS INDEX

Climate change and sustainability have become key topics post-COVID-19 and at the recent COP26 climate change summit. Legislative policy changes and societal pressure are calling for companies to undergo a strategic realignment. Such fundamental drivers have moved the e-mobility topic up the strategic agenda for automotive executives worldwide. Of course, climate change is a controversial topic and has caused heated dispute over the last few years but has received strong interests from corporate leaders and politicians across the globe. The COVID-19 pandemic and the global warming issue have further pushed governments to take action and business operators to rethink their missions to become more sustainable. One key solution would be to prioritize the EV industry.

Countries have different requirements for EVs and approaches for realizing the true EV potential. Understanding these differences would allow governments to implement a “once in a century” disruption, like switching from fossil liquid energy to electric energy, and automotive leaders to invest in future mobility services, like transitioning from ICE vehicles to EVs. To assist executives in automotive organizations of all kinds around the world, ADL has set up a methodology to evaluate the “readiness” of markets for electric mobility. Such a metric enables a solid understanding of the current situation. The standardized approach and evaluation metric allows for a comparison across markets toward overall readiness.

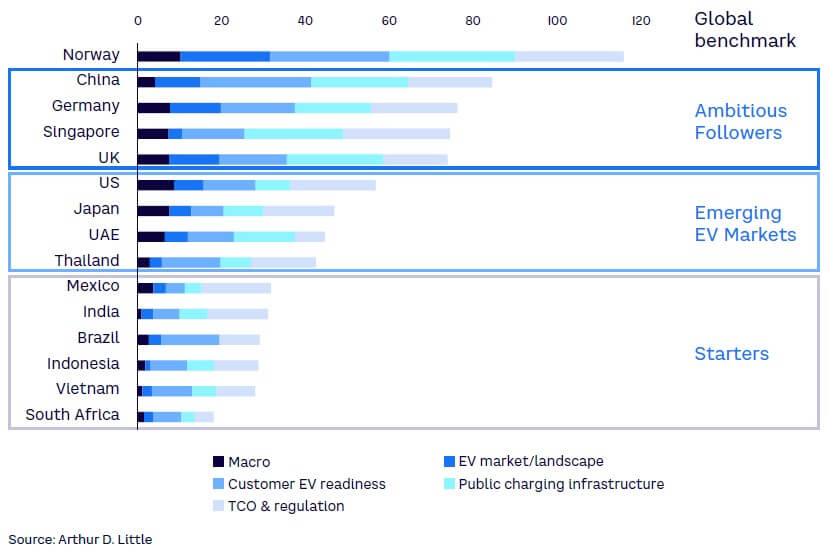

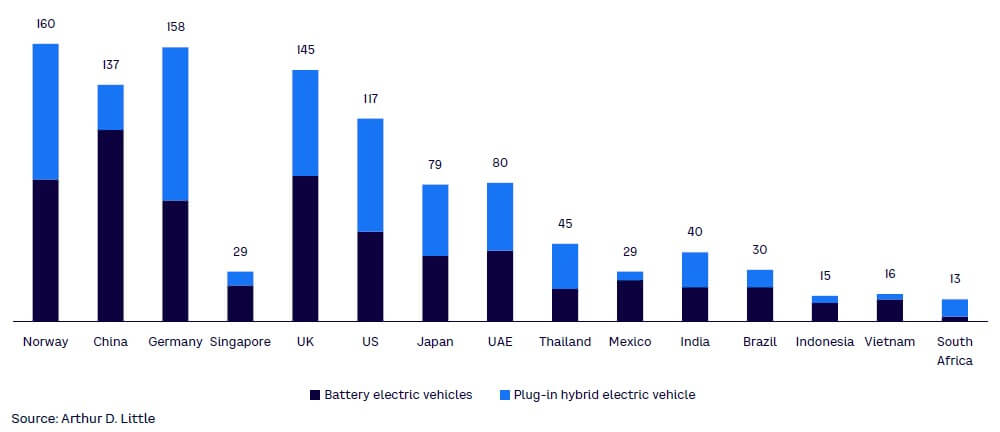

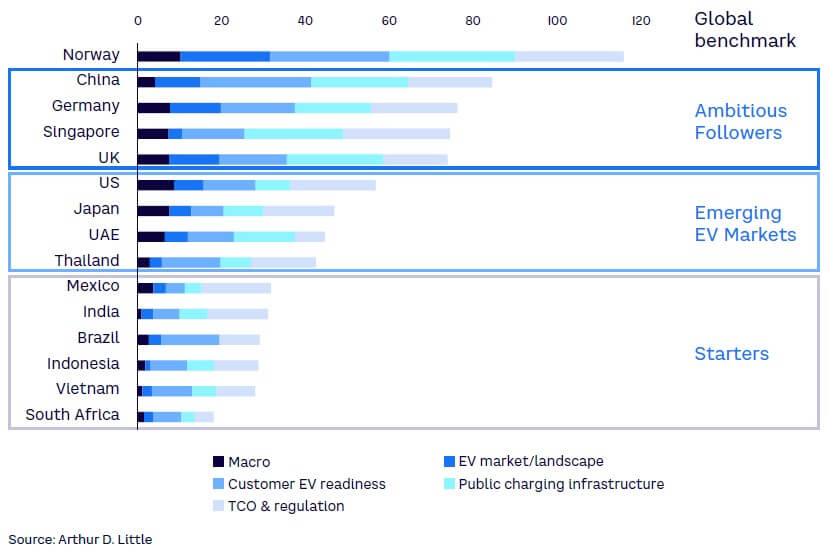

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the key results of ADL’s Global Electric Mobility Readiness Index (GEMRIX) 2022 edition regarding the analysis of Thailand. In summary of GEMRIX 2022, Norway is the EV leader, with a score of 115. Next comes China, Germany, the UK, and Singapore, where all prerequisites for e-mobility are in place and EVs are on the verge of becoming mainstream. These countries are followed by the US, Japan, the UAE, and Thailand. Here, EVs are still inferior to ICE vehicles, even though customers are becoming more comfortable with the idea of EVs as infrastructure is ramping up. Lastly, Mexico, India, Brazil, Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa have just entered the game and face major challenges in costs and infrastructure.

GEMRIX METHODOLOGY

GEMRIX by ADL has been calculated for Thailand and 14 other countries in the current 2022 edition and gives a comparative picture of Thailand against other markets. The index has been calibrated around a notional threshold value of 100. A score of 100 implies that market readiness for e-mobility is on par with ICE vehicles across relevant buying criteria, such as costs, utility, and availability. Thus, a score beyond 100 shows that EVs are even more beneficial than ICEs. Market readiness is evaluated in five major categories that drive EV adoption: macroeconomic market factors, EV market and competitive landscape, customer EV readiness, public charging infrastructure, and TCO and regulations. Each category consists of six to 15 specific data points, which were analyzed with a standardized metric for each country, rendering a total of 45 variables per country.

The five categories were weighted regarding relevance for EV adoption. Markets can score a different number of points in each category and vary according to the weight of the category and their market data. The individual point score is calculated based on analytics that consider relative and absolute performance measures. The final index score is the sum of performance indicators from the five sub-categories. This allows a detailed evaluation of a Thailand’s e-mobility readiness.

GLOBAL E-MOBILITY READINESS DISTRIBUTION

Markets around the world are at three levels of readiness (see Figure 25) with only Norway having achieved full readiness. With a score of 115, Norway clearly makes EV the better choice in the country. The index is designed to compare the market conditions for EV and ICE vehicles. An EV readiness score of 100 means that in a given country it is equally beneficial to buy and operate an electric vehicle as one with an internal combustion engine. Higher values indicate advantages for EV, while lower scores mean benefits for ICE. The remaining benchmarked countries can be broadly categorized into three clusters as to their readiness:

- China, Germany, UK, and Singapore are Ambitious Followers, with around 80 points. In these countries, switching to EV is no longer only an option for some enthusiastic pioneers; rather, it’s becoming a valid choice for the mass market. In the near future, all four countries have a concise political agenda to reach equality between EV and ICE. Driven by this agenda, the industry is gearing up in the respective countries. Consequently, consumers have seen a major jump in recent years in the number of available EVs and charge points.

- The Emerging EV Markets in the US, Japan, the UAE, and Thailand scored between 40 and 60. These markets still show significant drawbacks financially as well as in ease of operation for EV over ICE. However, all of them are heavily investing in electric mobility and will most likely catch up soon. A special role in this group is played by the US. As the home of EV pioneers like Tesla ventures out to electrify the world, the US scored roughly 10 points more than the other countries in this group. The US is in a unique position, as the prerequisites for EV in East and West Coast states are very good, while in large parts of the country and much of the population, especially in the central states, ICE cars remain the emotionally and economically preferred option.

- Finally, we see a group of Starter countries, comprised of Mexico, India, Brazil, Indonesia, Vietnam, and South Africa. In these countries, electric mobility is beginning to enter the conversation; however, given their socioeconomic position, EVs are not a priority among politicians seeking election. In these countries, choice of vehicle is driven more by cost and utility considerations than by green aspects. Accordingly, we see an uptake in areas where TCO of EV starts to be equal or even better than ICE. Currently, this appears in the 2W and 3W space, which in those Starter markets accounts for a significant share of the overall market.

MARKET READINESS

Industry players in each country contribute significantly to the attractiveness of EVs to customers. The number of vehicles offered and how they are brought to market can spark the interest of consumer or can prevent them from even thinking about EV if the offer is not attractive. This involves a combination of factors, including the number of products offered and the segments covered by them, product quality, design and concept creativity, as well as pricing.

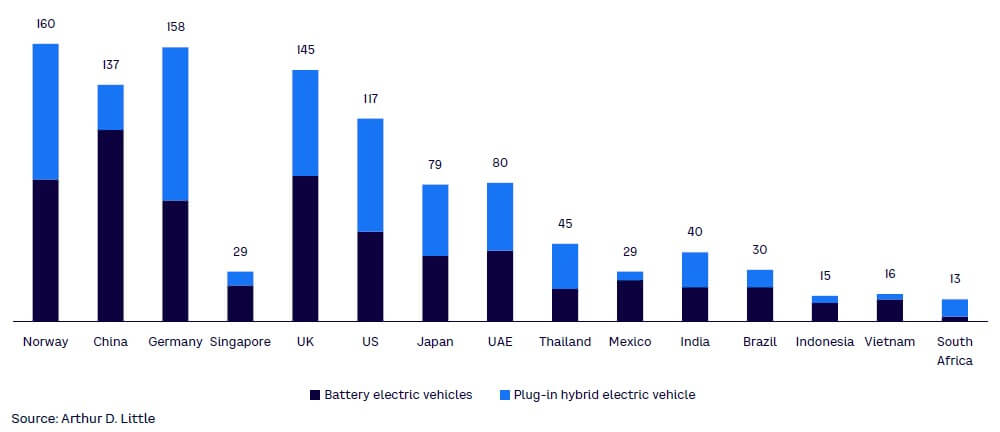

Norway is the only benchmarked country with an EV sales share of more than 50%. Among Ambitious Followers, EVs have a comparatively low sales share, approximately 15%-25%. Leading markets have a range of EV models with six countries having more than 75, led by Norway and Germany. However, for globally acting OEMs, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Manufacturers need to ensure supply while crafting individual sales strategies for countries based on readiness of each market. Thailand has close to 45 models (see Figure 26), but most of these models are PHEVs. Only 19 models are in the EV category. A shift toward a higher number and a greater share of models that are purely battery EV is indicative of a more mature EV market. This is yet to be seen in Thailand, given that major incumbent OEMs are Japanese with a more dominant portfolio toward PHEVs and HEVs. However, given recent market movements discussed in Chapter 2, this outlook is expected to change.

Besides traditional OEMs, new players are also entering the EV market with their own product launch. As discussed earlier, European and Chinese OEMs are ramping up e-mobility, while new players are also coming onto the electric mobility scene.

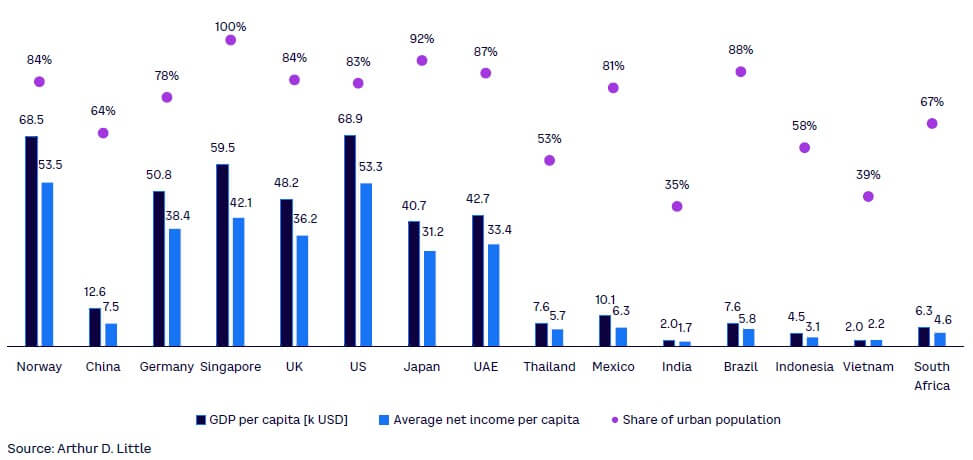

CUSTOMER READINESS

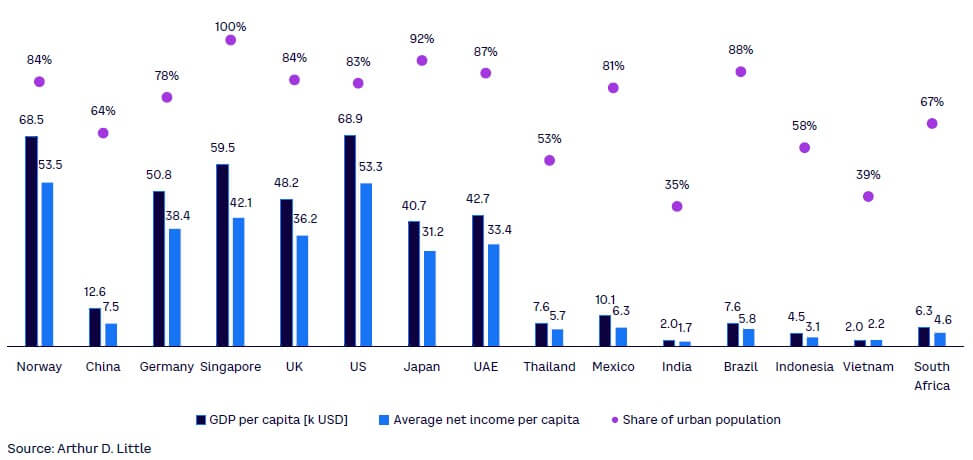

Customer adoption and readiness does not depend only on objective factors like availability of charging points but is also a subjective matter influenced by personal preferences and the perception of EV. Cost is one of the most important factors. This poses a challenge for developing countries such as Thailand, since EV prices are still high and income is comparatively low. Thus, OEMs need to decrease cost while government needs to create an incentive to influence the success rate and allow customers to enjoy electric mobility. Broadly, the readiness of customers to buy an EV is determined by their willingness and ability to do so. Ability comes down to accessibility and price. Even though prices have fallen in general, in many countries investing in an EV is a major purchase decision due to low income levels.

In Thailand, the average yearly income is US $5,716. Although various ICE cars are available, the cheapest is in the range of US $9,000-$12,000, a cost barely affordable given income. The cheapest EV car in Thailand starts at US $22,856 (post-subsidy). At that price, electric 4Ws are not accessible by the general public. As for 2Ws, however, prices are much more attractive. The cheapest ICE scooter is available at US $900, and the electric scooter is available at a similar price. Additionally, a scooter can be charged using a standard household plug, while a car would require the installation of a wall box or a public charging pole, an additional hurdle for the average customer in Thailand.

The topic of charging naturally leads us to accessibility. In ADL’s study, we see a correlation between the share of population living in urban areas and EV readiness (see Figure 27). Lack of access to public charging infrastructure is a massive hurdle to the adoption of EV. Globally, the density of public charging points in rural areas is nowhere near the density of petrol stations. With most EVs still of lower range as compared to their ICE counterparts, countries with a large rural population like Thailand have a significant challenge to solve. Again, this hurdle is much less pronounced for electric 2Ws, which can effectively be charged using standard household power lines.

Concerns about environmental protection play the second most important role in readiness to buy an EV. We see a clear correlation between EV readiness and environmental awareness, as measured primarily by the number of governmental activities and the number of years since those activities were introduced. Countries like Norway and Germany have focused on sustainability issues for quite some time; Thailand, however, only has recently committed to a carbon neutrality target and made decarbonization of transport sector a priority.

In summary, GDP and income levels indicate if a market is driven primarily by cost or if other societal trends like environmental sustainability play a role. In Thailand, GDP and income-related factors still dominate; hence, cost is key as an enabler of customer readiness.

INFRASTRUCTURE READINESS

Infrastructure readiness primarily comes down to availability and performance of charging options (i.e., number, distribution, and quality of public charge points). Even in the benchmark market, Norway, most EV charging still occurs through private options. However, a dense public infrastructure lowers psychological barriers for customers and increases EV usability. It is also a precondition to reach customer segments without private parking and charging opportunities. To evaluate infrastructure readiness, types of chargers (AC, DC, and high-power charging), number of chargers and geographical distribution and coverage were considered.

For infrastructure readiness, battling range anxiety — the fear that a vehicle’s battery will not have sufficient charge to reach the destination — is a key issue. DC chargers are the right bet, as they lower charge time, are perfectly suited for highways, and decrease range anxiety. Before market solution and entrepreneurial players for charging infrastructure can arise, the government needs to invest to support development. Charging infrastructure is critical for customer adoption of EVs. While targets for DC charging have been announced in Thailand, the government needs to study different charging business models and identify relevant data points to develop a commercially viable business case for financiers. As noted in Chapter 3, our market survey of Thailand revealed that 50% of respondents were opting not to purchasing an EV due to issues around range anxiety, while another 32% cited difficulty in finding a charging station (refer back to Figure 21). As of September 2021, there are a total of 1,511 AC outlets over 640 locations and 774 DC outlets over 250 locations. Overall coverage of area is 1%, which is low. This is one of the reasons for EV sale penetration being so low (0.2%).

However, consistent efforts are being planned for building the charging infrastructure. The Ministry of Industry, for instance, has targeted setting up charging stations that are no further apart than a 50-70 km radius in years to come. To bolster this, three SOEs — Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand, Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA), and Provincial Electricity Authority (PEA) — have come together to lead investment in the EV charging infrastructure.

While in the nascent EV market, the availability of private charging at home and the workplace is the key enabler, as EV adoption picks up, focusing on the public charging infrastructure is critical. Only a feasibly dense and easy-to-use public charging infrastructure will allow long distance travel by EV to be possible, which is especially important in Thailand given the poor public transport infrastructure, a mixed use of vehicles for personal and business travel, and a decent share of rural population. Within the public charging infrastructure, DC charging should be prioritized as current maximum output power can reach up to 300 kW. Typical DC charging of 50 kW can be sufficient to refill a typical EV battery of 40 kWh (e.g., Hyundai Ionic) in less than hour. As Thailand builds its public charging network, it should prioritize DC charging over the next few years, so that as affordable EVs come to market, charging as a challenge is addressed effectively.

GOVERNMENT READINESS

Government readiness hinges on a government’s willingness to take the first step by introducing wide incentives for purchasing vehicles. Customers should not pay a premium for EVs. Moreover, governments need to reduce TCO via demand-side or supply-side incentives.

Legislative and regulatory bodies play a central role in shaping the market for EVs. The entire ecosystem around ICE vehicles has evolved and was optimized for more than a century, supported by unimaginable investments and subsidies. Without specific incentives and legislative interventions, it is next to impossible to overcome this head start in the time required for climate protection. Different governments have used different approaches to incentivize EVs and/or disincentivize ICE vehicles. Betting on EV is no longer a risky gamble.

ADL analysis shows that incentives work in many countries. Especially when looking at the combined number of subsidies offered in different countries, we see that the countries that have had higher subsidies for a longer time generally score higher in ADL’s readiness index.

Sales incentives are clearly capable of moving the entire EV industry forward. Thailand offers various demand-side incentives to consumers, such as the following:

- Sales price incentives. At time of purchase, the demand subsidy ranges from US $1,907 to $4,087 (see Figure 28), depending on model, vehicle type, and battery capacity.

- Ownership incentives. There has been a reduced excise tax from 8% to 2% for imported EVs.

- Operations incentives. There has been a 40% reduction in import duty for CBU EVs priced up to US $61,805 and a 20% reduction in import duty for those priced between US $61,805 and US $211,278.

Besides these incentives, the Thailand government is also offering a five-year CIT exemption for investments in charging stations with at least 40 chargers (25% of which are DC type). In the medium term (2024–2025), it is expected that the government will focus on promoting domestically manufactured EVs while also removing some benefits for imported vehicles. Overall, we believe the government has made the right moves with a good mix of demand-side and supply-side policies.

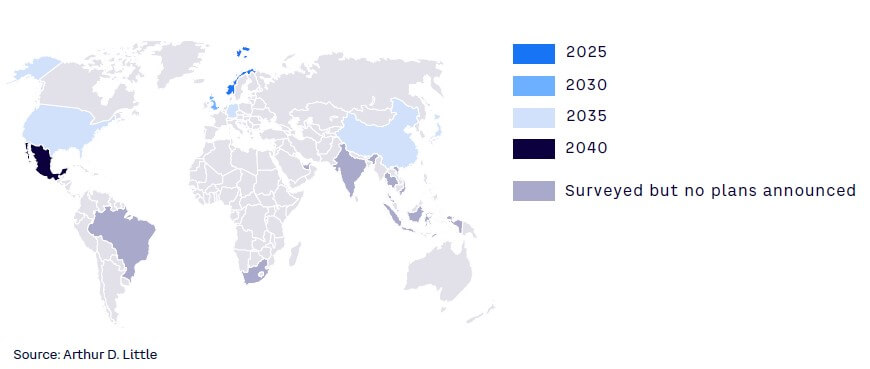

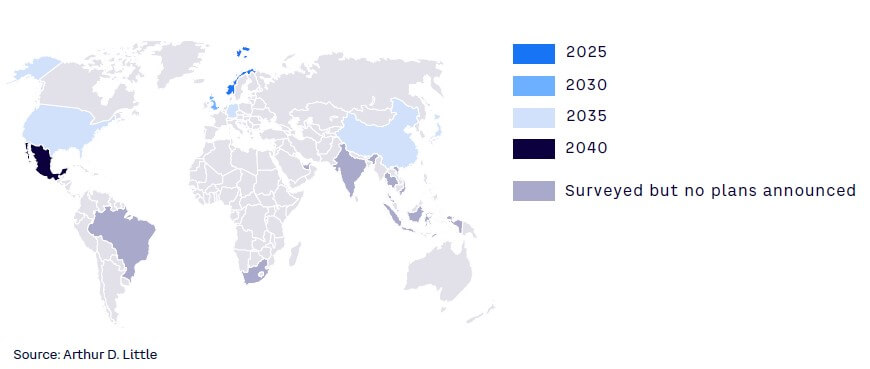

Governments around the world have initiated another policy-related announcement to bring forth much needed clarity for the business community — enforcing the end of fossil fuel engines. Norway will be the first country to ban ICE passenger cars from 2025 onward. Other markets have made similar announcements (see Figure 29). Although Thailand is aiming to only sell zero emission vehicles domestically by 2035, realization of such a bold move depends on the punitive measures that may be announced if domestic producers do not adhere to such regulations. The ICE industry is a high source of employment for the Thailand economy; with the EV market still developing, it’s unlikely that the policy would be implemented with strict enforcements and the timeline is likely to be flexible. Alternatively, the government should consider operational incentives for EVs, which relates to the subsidized cost of EV charging, reduced tolls, subsidized parking prices, exclusive parking, dedicated lanes for EVs, and so on. Importantly, MEA plans to lower electricity prices for EV charging for the first two years at a subsidized cost of US 7.2 cents per kWh to be offered between 10 pm to 9 am (off-peak hours), while the regular price of US 13 cents per kWh would prevail during other periods. Such policies should be encouraged and implemented along with integration with RE sources.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

The Electric Mobility Readiness Index for Thailand classifies it as an Emerging EV Market. Such a classification has implications for OEMs (vehicle manufacturer) and infrastructure providers. OEMs need to utilize a special planning method and a viable market entry strategy. They should opt for a selective offering by first targeting the most promising customer segment (lower risk) with the understanding that the new offering is only part of market preparation. Focus should also be on developing the entire EV ecosystem — upstream supply chain, components, and charging infrastructure.

5

THAILAND’S EV EVOLUTION & REALIZING THE EV DREAM

Certainly, the Thailand government has made bold plans in unleashing the EV evolution. As discussed in Chapter 2, various regulatory and market movements are playing a role in this pivot. To analyze the overall offtake in EVs by the end of 2030, ADL has examined some of these regulatory and market changes. Based on ADL’s assessment, we conclude that the Thailand government will likely miss its target of 1.123 million ZEVs by 2030. As a result, we propose some key recommendations for the government to consider.

ADL has analyzed the EV market in depth, by understanding the current situation as well as outlining market movements and regulatory analysis. In the process, a few challenges have been identified. In this final chapter, we provide an assessment of the projected growth in the EV sector in Thailand along with some key factors that explain the growth trend observed and the implications the government should consider in terms of its areas of focus in order to realize its EV dream.

ADL EV ASSESSMENT

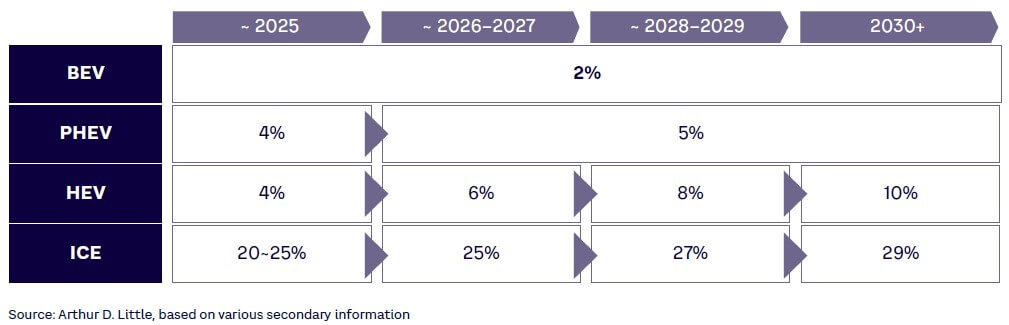

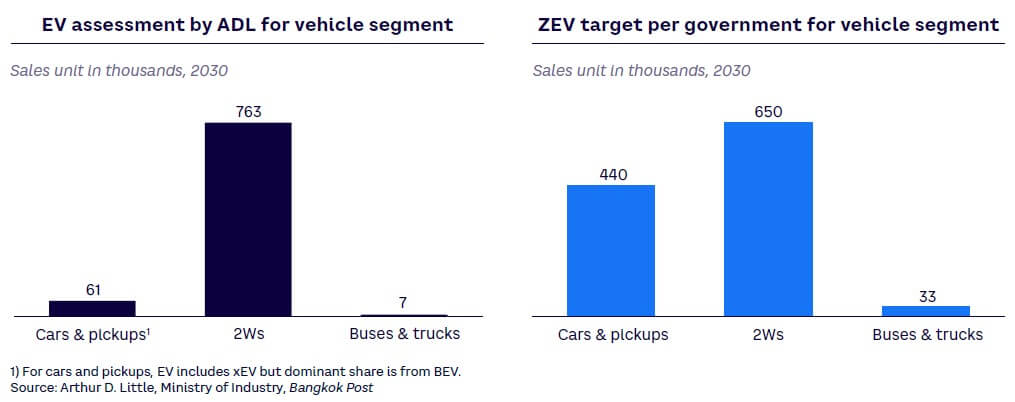

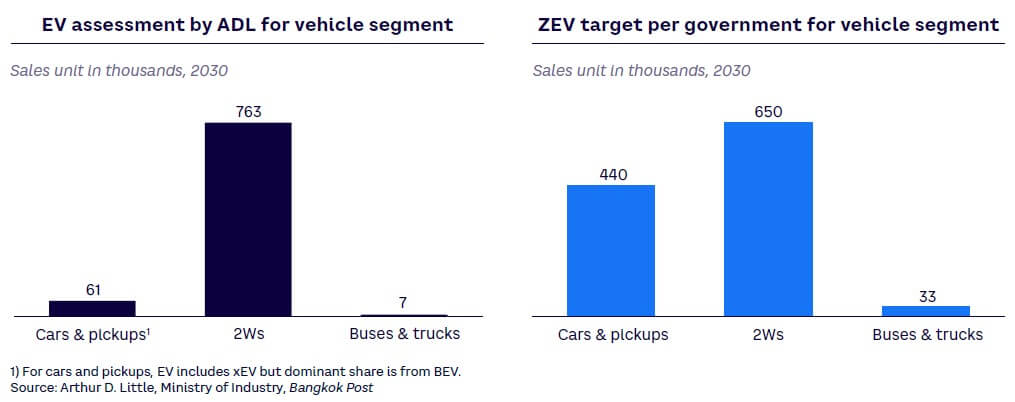

The sale of EVs in Thailand is expected to increase from just 1,572 units in 2020 to about 831,161 units by 2030, registering a 529x increase overall (see Figure 30). More specifically, the vehicle segment adoption rate by 2030 is projected to be 61K units for cars and pickups, 763K for 2Ws, and 7K for buses and trucks. Compared to the ZEV target for 2030, we notice that only for 2Ws would Thailand meet its target; it would not achieve its target for cars, pickups, buses, and trucks (see Figure 31).

Electrification by 2Ws would exceed the government’s target, given the strong push by both the homegrown brand and Chinese brand, which look to exploit the growing electrification trend. The price gap between electric 2Ws over ICE is less steep; hence, it’s easier to overcome TCO considerations. Success of this vehicle category to be electrified is closely tied to how innovatively the electric 2W OEMs introduce vehicles with different ownership models, exchange programs, buyback programs, private leases, and deals with financial institutions to make buying and owning an electric 2W accessible.

Buses and trucks may be difficult to electrify as the extra weight of the batteries for those types of vehicles has a direct impact on the payload carrying capacity. Electrification of such vehicles directly depends on the network of the DC public charging infrastructure, which is expensive and may not be set up until the end of the decade. Moreover, Thailand has a biofuel policy and active blending may be encouraged in higher commercial vehicles.

Finally, electrification in cars and pickups is expected to face strong resistance from their ICE counterparts and mass market brands until 2030, impacting the vehicle offtake in this segment. As incumbent OEMs may be less reluctant to promote the EV trend, the government can introduce its EV target obligation for each OEM and consider strict enforcement and punitive measures if such targets are not met. The Thai government target of 1.123 million ZEVs is closely tied to electrification in the car and pickup segment as other segments have either reached a certain electrification level (2W) or may face difficulty in electrification due to technological constraint (commercial vehicles) and the potential of alternate fuel applications (biofuel or otherwise).

EXPECTED MARKET EVOLUTION

The ADL assessment showcases overall EV sales at 831,161 which is lower than the government’s ZEV target in 2030. Next, we briefly discuss the factors contributing to EV adoption, which range from regulatory to business, social, and economics-based factors, and map expected EV evolution and offtake.

Focused policy play

The Thai government has approached its EV policy with an integrated focus, offering significant demand-side and supply-side incentives covering the necessary components and charging infrastructure. Such policies would provide players and consumers with confidence in the government’s commitment. Moreover, overarching policies, such as a commitment to carbon neutrality by 2050, provide an indication of the government’s overall direction. EV entrants are exploiting these policies to develop new products or services, which typically have a lead time of two to three years before sufficient scale is attained. Hence, we expect a real thrust in EV adoption from 2025 onward.

Lead time for capability building & consumer preferences

Much of EV activity is being led by nontraditional players, whose primary activity has been outside the automotive industry. Such players are testing the market with different solutions and building capabilities in new business areas. Based on ADL’s prior experience in other markets, developing such capabilities requires four to five years. During this period, not only are the new entrants building new capabilities, but they are also countering competition from traditional incumbents. Moreover, a few years’ time is needed for consumer preferences, behaviors, and attitudes to change, which is closely linked to the activity of market participants.

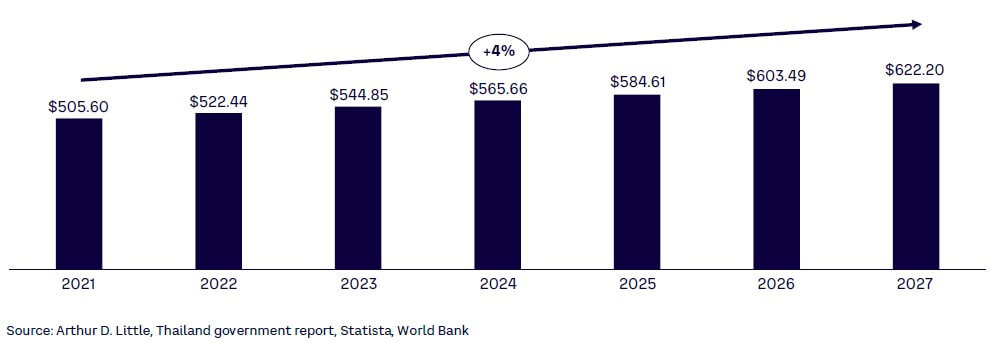

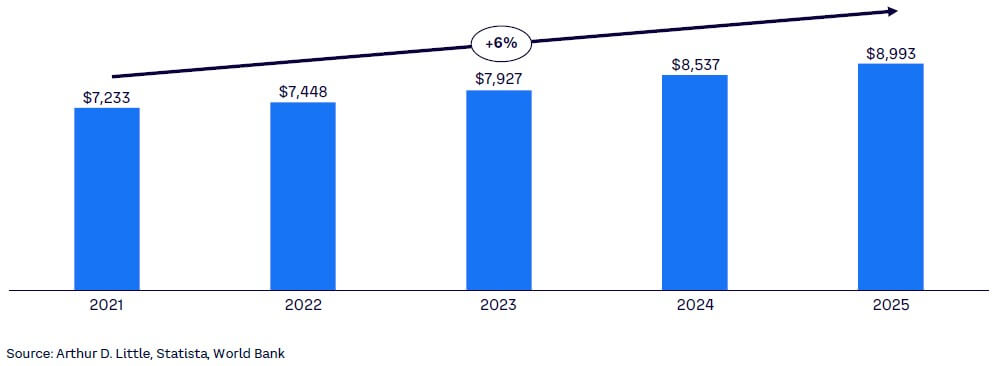

Growing income resulting into higher affordability for EV